BC students in a bean field, Morrisville, NY, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

In 2000, Brooklyn College Professor Adina Back interviewed alumni who participated in the Farm Labor Project. These oral histories along with newspaper articles and newsletters found in the Archives present a more balanced picture of the two years at Morrisville, one which challenges the official College version of happy students toiling in the fields. While no first-hand student recollections have been found from 1942, Professor Back’s oral histories reveal that some of the students who spent the summers of 1943 and 1944 upstate became disillusioned. Unfair treatment in the fields, the willful destruction of crops, and racism led to strikes and protests, all to the dismay of Professor Benedict, who held radical students partly to blame for the demise of the program.

In April 1944, the Vanguard student newspaper published an eye-opening exposé titled “1943 Farm Project Leaves Room for Improvement: Sour Note Produced by Non-Cooperation; Result: Distrust, Disrespect, Disharmony.”1 This article and subsequent follow-up stories enraged Prof. Benedict, who wrote “A smear story in the Vanguard, and the failure of the College paper to contribute any real support was probably a definite factor in the slump from the 1943 figures. It may be added that this slump in registration was a definite adverse factor which worked against 1945 planning.”2

Article from the Vanguard about the 1943 Farm Labor Project, written by Louise Schneider and Marion Isaacson (Greenstone). Brooklyn College Newspaper Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

According to the Vanguard, the purpose of the April 1944 article was to prevent the errors of the previous summer from being repeated. In the article, students who participated in the 1943 project attributed most of the problems to Benedict and other faculty members who viewed students with “suspicion and distrust” and were interested only in the number of bushels produced: “When some pickers, after twelve continuous days of hard work, felt that they needed a day of rest because of extreme fatigue, they were made to feel like shirkers.”3

An evening class at the Morrisville Institute, circa 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

Alumni interviewed by Professor Back recalled the long hours of manual labor with both students and faculty exhausted from the long days spent in the fields. Elliot Levine ’46 recounted how students fell asleep in geology class out of sheer exhaustion.4 Frances Goldberg Koral ’46 added that her professor, who supervised the students as they harvested the crops, “was as tired as we were. And you couldn’t flunk anyone, and we did the minimum of what he required, and he required the minimum.”5 This sentiment is reiterated in the Vanguard article: “Many students, nevertheless, found that they were unable to study properly. Classes after a long, hard day of work were often too heavy a load.”6

A BC student carrying two empty bushels into a bean field,1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

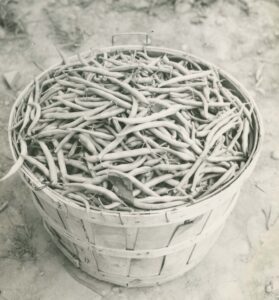

Filling bushels with peas and beans was backbreaking. According to Marjorie Meyers Brockman ’46, “you had to pick thirty-two pounds to make sure the bushel was crowned. And some people, ’cause it was hard, I mean, thirty-two pounds of string beans is a lot of string beans, and you had, if you wanted to support yourself and pay for your food and housing, you had to pick many bushels a day.”7 Brockman, like many other students, had to ask her parents to send money from home to cover expenses. Elliot Levine’s father sent him ten dollars from home, but after a few weeks his skill at picking beans improved enough that he did not have to use the money to pay his bills.8 Others fared better. Eva Solomon Ziesk ’45 possessed enough skill and stamina to cover her room and board: “A lot of the students who were on this trip with us had to send home for extra money. And it was a point of honor with me that I was able to support myself and any expenses I incurred during the summer.”9

Professor Vernon Booth supervising BC students, 1943 Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

Frustrations also mounted over poor field conditions. Students complained about not being assigned to the best fields or being placed in fields where the plants were being picked over for the second or third time. Elliot Levine remembers that following a lecture on government subsidies, he and his roommates wrote to Professor Benedict proposing that the assemblies be about the problems the students were facing, especially not being able to pick enough bushels to pay their bills. This and other unresolved issues led to student protests. According to Levine, “There were walk-offs. People would walk off the fields in protest…We could not make enough money out of it, and I remember Mr. Booth (Geology professor who supervised students in the field) saying, ‘from now on anybody who walks off the field can walk right back to New York.'”10

The students struck on August 23, 1943 to protest the inadequate use of their labor. While working in one of farmer Grove Hinman’s fields that had already been picked over two or three times, students were told to only work a half-day due to poor crops: “We knew that here was a waste of labor, money, and machinery because we were put to work on Mr. Hinman’s third and fourth pickings (poor crops), while other farmers’ first pickings were left to rot in the fields.”11 Benedict denied the students’ request to be assigned to other farms. Despite contacting the United States Employment Service and the efforts of the newly formed Morrisville student council, “In the end, we went right on picking for Mr. Hinman during the remaining few weeks, disgruntled and disillusioned.”12

Hinman provided trucks to transport BC students to and from his fields, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

Margorie Brockman recalls striking for several reasons, calling it a “Grapes of Wrath situation.” For Brockman, “It was just a concentration of negative things: the housing for the black workers, the beans being dumped, and the fact that he (Hinman) was making a lot of money out of this practically free labor he was getting and that wasn’t the proper division of wealth that was for sure.” Brockman recounted how one afternoon on the way back to the Institute, she and others saw overseers dump the crops that the students had picked into the river. “I remember going on strike in the middle of the season…we had discovered that the beans were being dumped into local streams and rivers because it did not pay for him (Hinman) to expend the gasoline, which was also rationed, to ship them down to New York since beans were getting such a low price on the market and that infuriated us. It enraged us.”13

Both Margorie Brockman and Frances Koral also described the poor living conditions and unfair treatment experienced by the Caribbean migrant workers who toiled alongside them in Hinman’s fields. Brockman stated that the migrants were housed in chicken coops and not even given ladles to drink water. Instead, they had to use their hats or their hands.14 Koral added that “They were being paid much less than we were paid.”15

Benedict, in several reports and publications, wrote about workers from the Bahamas who were living in an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp in Morrisville. Because of the farmworker shortage, including the lack of African-American migrant workers from Florida who had harvested crops in upstate New York before the war, the Federal Government flew in temporary workers from Mexico, Jamaica, and the Bahamas. Benedict was proud of the fact that the Brooklyn College students were a more economical option. While the Bahamians were better pickers, Benedict argued that if the price of plane travel was included, the labor cost for the Bahamians was $1.25 per bushel, while the BC students cost only 10 cents per bushel.16

A 32-pound bushel of beans, circa 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

For Marion Isaacson Greenstone ’46, the BC students were “trying to get more money and not be exploited. After all, we were radicals from Brooklyn. But nothing much ever came of it.”17 There were, however, some small victories. The Vanguard reported that after Hinman changed the weight requirements for the bushels based on field conditions, the students asked for a scale. Benedict denied the request. The students, however, did not give up and petitioned the farmer directly to get their scale.18 Frances Koral described how sometimes the crown (top of the bushel) had to be five inches high and sometimes seven. She recalled that students told the BC professors at Morrisville: “We’re your Brooklyn College students, and when we go back, and we tell them you permitted us to be cheated by the farmer, you’re going to be in trouble.”19

Another victory, although hollow, was the election of a student council in Morrisville. Upon arriving in Morrisville in 1943, Benedict refused to entertain the students’ request to elect a student council. His reasoning: elections could not fit into the tight schedule. Students countered that elections could be held at the beginning or end of the compulsory Friday night assemblies. In an editorial in the student newsletter, the Beanstalker, Marty Liftin and Ruth Schektman wrote, “A student council would enable us to express to the faculty our suggestions and difficulties…it is imperative that some representative body, which can speak for us and be a link between the faculty and the students, be elected immediately.”20 According to the Vanguard, it took five weeks of pressure for elections to finally be held. But once the student council was in place, “the faculty neglected to cooperate with it and ignored most of its requests.”21

Full bushels ready to be collected by Farmer Hinman, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

In late April 1944, a group of 1943 students submitted a report on Morrisville to a faculty-student committee “outlining remedies for last year’s shortcomings,” particularly the election of a larger student council with the power of self-government and voice for student complaints.22 The Vanguard article and the student report seemed to affect the 1944 Project. Professor Benedict announced that Hinman purchased additional tractors, which would be used to collect and transport full bushels, eliminating “the need of toting full bushels long distances to collection centers.” It was also announced that student participation in Friday night assemblies would be permitted.23

Although the tractors never materialized, the 1944 students did create a system for lugging the bushels. There were other improvements in 1944 including a rest period, quitting time set at 4:30, no work on Sundays, an active student council, and conferences with farmer Hinman. Students did complain about the lack of a nurse on-site and that the long hours of work still interfered with studying.24

1944 also saw its share of student unrest. In a report to President Gideonse, Benedict wrote of the students that there were “fewer agitators than last year, with 25 from 1943 generally working out as we hoped, to carry forward something in the line of traditions, for dorms, and fieldwork, etc. In these respects, achievements have been average; expected leaders have missed on responsibilities; in some cases, assumed that they could break the rules, etc., but the old group has indicated a real feeling for the Project. In times of possible agitation, some of the 43 group have stepped forward, explained things, etc. Dispositions to leave the field in threatened rain, etc., have been stopped.”25

BC students picking peas, circa 1944. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

In Benedict’s August 7, 1944 memo to Gideonse, he described a work stoppage on a sweltering day after a week of poor pickings: “One afternoon, after a mid-afternoon shift, the students refused to pick. It was mild, and the field staff were sympathetic, and fortunately has had no repercussions, although it happened that that afternoon press photographers and Farm Bureau people visited the field during the ‘rest’ period. As a result of combined action, staff and students, a conference with Hinman yesterday, closing time is to be half an hour earlier.”26

BC students exploring the area around Morrisville, circa 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

Despite problems, students enjoyed the freedom of living away from home, socializing, dancing at the local Grange, and exploring the area around Morrisville. While Frances Koral recalled many negative aspects of the project, she concluded that she still had a good time, remembered attending square dances, hanging out with friends, and popping corn: “I came home exhilarated. I had a marvelous summer.”27 Eva Ziesk signed up for Morrisville to contribute to the war effort and overcome her shyness and learn to be independent. She spoke fondly of the long-lasting bonds of friendship formed at Morrisville: “I do remember vividly the fast relationships that grew up because you were on your own and people in the fields were helping each other. After you stopped working there were all sorts of conversations.”28 Even 57 years later Marion Greenstone was still friends with Marjorie Brockman and others she met in Morrisville. She credited their political affinity with both the start and continuation of their friendships.29

BC students pose in front of a waterfall, Morrisville, NY, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

The front page of the July 1943 issue of the Beanstalker. Brooklyn College Photographic Collections, Brooklyn College Archives.

The vibrant social life the students created between long workdays and evening classes is evident in the few surviving copies of the Beanstalker. The tone of the newsletter is, for the most part, lighthearted, with social events dominating the pages. In the July 23, 1943 edition, there is a section devoted to lists of couples spotted together in town. A colorful description of a picnic that included swimming and singing concluded that “not even the unorthodox combination of frankfurters and ice cream could spoil anyone’s fun.” There was also an announcement that Jewish religious services would be held on Friday nights. One student entrepreneur even posted an advertisement: “Bothered by bugs? Get ersatz screens of mosquito netting at 25 cents a yard.”30

The Beanstalker continued to be published during the fall 1944 and spring 1945 semesters. Articles in the December 6, 1944 issue called on students to help with the faltering 1945 recruitment drive. This issue and subsequent ones also provided information on participants now serving in the armed forces and announcements of marriages and engagements.31 In February 1945, the Beanstalker asked Farm Labor alums to fill out a questionnaire with responses meant to “find the weak points in the work-study program, with a view toward correction.” However, because only a small number of questionnaires were returned, no conclusions could be drawn.32

Although the Beanstalker sponsored recruitment events, the tide had turned against the continuation of the project. But the memories and friendships remained. Even the Vanguard’s exposé of the 1943 program concluded with a passage supportive of the project: “But positive aspects of the project cannot be overlooked: most of our time in the sun and air, the glorious scenery of the countryside, the companionship of the dormitories, and, above all, the completely new life we learned to lead, was both valuable and enjoyable. The students learned greater self-reliance, in that many of them were made to take care of their own financial affairs for the first time, learned to attend to their own rooms, and personal effects (this includes cleaning and washing heavy work clothes.) The attempt at self-government, contributed in a measure, to this maturity.”33

BC Students washing their work clothes at the Agricultural Institute, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.