The struggle to establish a public college in Brooklyn started long before the Hunter and City College annexes opened in 1926. And since this is NYC, the fight was not only politically charged, but also a battle over Manhattan vs. Brooklyn control. After several bills failed to pass in Albany, the compromise Nicoll-Hearn Bill of 1926 paved the way for the creation of Brooklyn College in 1930. (See legislative timeline)

Rhetoric abounded over the decades with most politicians and business leaders agreeing that Brooklyn, with its growing population, needed a college. However, there was great difference of opinion regarding governance, location, and whether the new university should be a public or private endeavor.

Before 1930, private colleges existed in the borough including the Brooklyn Collegiate and Polytechnic Institute (1854); Long Island College Hospital School of Medicine (1860); Pratt Institute (1887); Saint Francis College (1884); Adelphi College (1896); and a short-lived Jesuit run Brooklyn College (1908-1921). Frederick W. Atkinson, the President of Brooklyn Polytechnic, argued that a free public college in Brooklyn under city government control was impractical. He believed that in order for a university to succeed, it needed tuition and a large endowment. 1

In 1905, Controller Edward M. Grout proposed a free university modeled after Hunter and City which would include Brooklyn Polytechnic, Adelphi, Pratt, and Long Island College. He noted like many others that there was not enough space at existing NYC colleges for the ever increasing number of Brooklyn students who had to travel long distances to campuses in upper Manhattan and the Bronx. 2 The sentiment to combine existing colleges with Adelphi College as the nucleus, was a popular one and put forth by politicians and Brooklyn ministers in 1911-1912 and lauded in a New York Times editorial.3 But these proposals more often than not called for tuition. (Hunter and City Colleges were tuition free, as was the entire CUNY system until 1976.)

Brooklyn Daily Eagle 10 April 1923, page 22, Brooklyn Collection-Brooklyn Public Library.

Some politicians were against the idea of free education altogether. In stating his opposition to the 1923 Reich Bill, which called for an independent public university in Brooklyn, Republican Assemblyman Walter Clayton said that he was not in favor of “building any more colleges for poor boys and girls,” and that founding of City College was a mistake. He concluded that “the next thing the poor will want us to do is clothe and feed them. This idea for free college is too socialist.” 4

While many prominent Brooklynites and politicians called for an independent public university free from City and Hunter, others argued that an autonomous public college was not practical. Twice during the 1920s, the New York Times printed editorials in favor of uniform administrative control for municipal colleges, a model which had benefited elementary and secondary education in the city. 5 Looking back on this debate, historian Willis Rudy concurred with the need for one administration, but for fiscal reasons. He wrote that if the bills calling for an independent public college in Brooklyn were approved, “it might well have served as a precedent for the reduction of City College and Hunter College to mere Manhattan institutions with the eventual emergence of ten distinct municipal college, with ten separate boards of trustees, ten charters, ten different methods of conducting educational work, and ten groups of representatives all competing before the Board of Estimates for funds.” 6

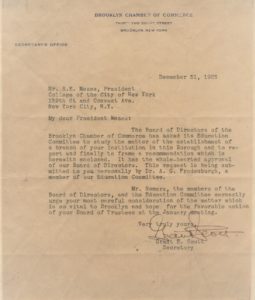

Letter from the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce to President Mezes, 29 December 1923, Brooklyn College Archives

Even the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce supported an expansion of City and Hunter into the borough. We uncovered two letters in the Archives from the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce to Sidney Mezes, the President of the College of the City of NY (City College). In these letters from 1923 and 1924, the Chamber asks for a meeting with Mezes to discuss the establishment of a branch of City in Brooklyn.

However, Brooklyn Borough President Joseph Guider’s mistrust of Manhattan politicians, along with his own political ambitions, fueled his opposition to the 1925 Nicoll-Hofstadter Bill which called for a college in Brooklyn controlled by a Board of Higher Education made up mostly of Hunter and City Trustees. He stated that since the majority of the board came from Manhattan, “they would not take much interest in a Brooklyn institution.” 7 Guilder’s competing Love Bill of 1925 calling for an independent public college stalled in the state legislature. The political divisiveness surrounding the Nicoll-Hofstadter Bill resulted in a veto by Governor Al Smith, which led to another round of legislative wrangling.

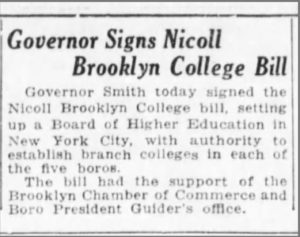

The bipartisan Nicoll-Hearn Bill of 1926 was finally signed into law on April 16, 1926. It charged a newly created Board of Higher Education with establishing a college in the borough with the most high school students. This borough was Brooklyn.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle 20 April 1926, page 7, Brooklyn Collection-Brooklyn Public Library.