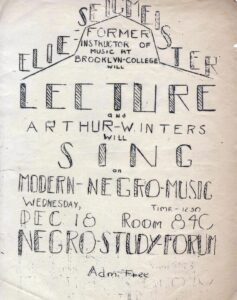

Flyer announcing a lecture by Elie Siegmeister. Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives.

During the mid to late 1930s, the Negro Study Forum and its evening session counterpart, the Negro Problems Club, sponsored events that not only brought attention to the racism inherent in American society but also focused on the cultural contributions of African Americans. One of the earliest flyers in the Archives announced an event in which composer and former Brooklyn College professor Elie Siegmeister spoke on “Modern Negro Music.” The Negro Problems Club, with assistance from the Harlem Art Center, sponsored an art exhibit in the Library featuring works by African American artists, including Jacob Lawrence and Ronald Joseph. Sculptor Augusta Savage spoke at the exhibit’s opening, which was “believed to be the first of its kind ever to be held in a metropolitan college.”1

In 1934, noted Harlem Renaissance artist and illustrator Aaron Douglas spoke about the contributions of African Americans to modern art at a Negro Study Forum meeting. That same year, the Forum held a symposium on discriminatory practices in education in which Richard B. Moore, a prominent African Caribbean communist, was the featured speaker. Moore stated that the “Negro student is already face-to-face with fascism in the south, where the landlords and capitalists are working to keep the Negro subjugated.” According to Moore, whites and African Americans needed to work together to “overthrow the oppression of the capitalist class and bring about the common ownership of the means of production.” At the meeting, members of the Forum passed resolutions to send a telegram to Fiske University protesting the expulsion of an African American student and to send telegrams to the Governor of Alabama and Judge William Washington Callahan concerning the Scottsboro case.2

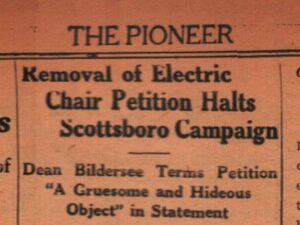

During the fall of 1934, the Negro Study Forum focused its activities on the Scottsboro case, culminating in the electric chair petition controversy. In November, Edward Kuntz of the International Labor Defense (ILD) spoke at a Forum meeting on the Scottsboro trial and the case against Angelo Herndon, an African American communist and labor organizer who had been arrested and charged with insurrection in Georgia.3 At this meeting, the Forum announced that it would raise money for the legal fees of both cases and was planning a college-wide Scottsboro protest.4

Part of the protest included a five-foot foldable plasterboard petition in the shape of an electric chair to focus student attention on the death sentences given to Heywood Patterson and Charles Norris, two Scottsboro defendants. While the Negro Study Forum believed they had received the proper permission from the Student Council to set up the petition in the Women’s Student Council room on Court Street, Dean Adele Bildersee disagreed. She called the petition, which 100 students had already signed, “a gruesome and hideous object” and ordered it placed in a closet until the Faculty Committee on Student Affairs gave permission for it to be displayed.5 The matter went again before the Student Council, who voted in favor of the chair. The archival record is silent on whether the Faculty Committee gave final approval or whether the chair petition was ever folded and mailed to President Roosevelt as intended.6 The Negro Study Forum held its Scottsboro Rally in mid-December, with Moore returning as the featured speaker. Moore stated that the Scottsboro case was an “example of the oppression of Negros, Jews, and workers.”7

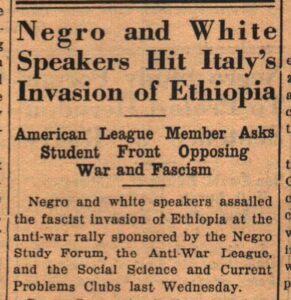

The Negro Study Forum also sponsored events related to international issues. On October 16, 1935, the Forum, the Anti-War League, the Social Sciences Club, and the Current Problems Club held a rally protesting the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Two hundred and fifty students attended. At the rally, students passed resolutions condemning Mussolini’s government and called for a boycott of Italian goods.8

Like its Day Session counterpart, the Negro Problems Club protested the Italian invasion of Ethiopia.9 Active beyond the campus, the Club sent delegates to youth conventions, including the American Youth Congress and the Brooklyn Youth Federation. In 1936, the Club undertook a study of juvenile delinquency in Brooklyn.10 They also sent petitions to FDR supporting the passage of the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill, hoping to get additional support from the Student Council and the ASU. Descriptions of the Negro Problems Club in the Beacon note its interracial makeup. In 1936, Jewish student and anti-war activist Perry Rosenberg ’40 was elected vice-president of the Club. Rosenberg would later become the president of the Evening Session’s Student Council.11

In 1936 and 1937, two notable undergraduates emerged as club leaders: Dollie Lowther Robinson as secretary of the Negro Problems Club and Muriel Robinson Baldwin ’40, president of the Forum.12 After graduation, Dollie Lowther Robinson became a distinguished labor leader who, early in her career, unionized 30,000 NY laundry workers.13 Robinson held government positions at the state and national levels and was the Special Assistant to the Director of the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor during the Kennedy administration. Active in local politics, in 1968 she ran against another BC alum, Shirley Chisholm ’46, in the Democratic Party primary to represent Bedford-Stuyvesant in Congress.14 In 1963, The New York Amsterdam News described her as “one of the most influential Negro women in organized labor.”15

During WWII, Muriel Robinson Baldwin ’40 worked as a junior professional assistant at the Signal Corps Laboratory at Fort Monmouth, NJ.16 After the war, civil rights groups pushed the NY Telephone Company to hire more African American workers. Following the passage of New York’s Ives-Quinn Anti-Discrimination Bill in 1945, the telephone company hired 300 African Americans, including Baldwin.17 Baldwin worked for the telephone company for more than a decade and later taught in the New York City public school system and at Kingsborough and Queensborough Community Colleges. In 2000, Brooklyn College awarded her a Lifetime Achievement Award.18

In 1938 Brooklyn College made strides in combating racism in athletics and theater. In January, the Brooklyn College basketball team played Hampton University–the first match in the country between a mostly white college and a Historically Black College and University. During halftime, the crowd approved sending a telegram to Congress supporting the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill. Brooklyn won the game, led by Jim Coward, the only African American on the Brooklyn College squad.19 In December, the College mounted a production of the 1927 Pulitzer Prize-winning play In Abraham’s Bosom.” It was the first municipal college to feature an African American cast.20

However, 1939 witnessed a setback when two chapters of the House Plan Association, a group of social clubs which were alternatives to sororities and fraternities, voted to exclude African Americans after members of the Negro Study Forum tried to join. This vote was condemned by not only the Negro Study Forum but also the Dean of Students, other campus clubs, and the Vanguard newspaper, resulting in an apology and a reversal from the House Plan Association.21 As war loomed on the horizon, the civil rights struggle would continue, with the war years bringing new challenges and opportunities.

Endnotes

1 “Elie Siegmeister Lecture,” Box 753, Folder 11, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Club News,” Vanguard 22 May 1936; “Art Exhibition,” Beacon 28 September 1938, 2; “Negro Art to be Exhibited,” Beacon 12 December 1938, 4. For more on Siegmeister, see Oja, Carol J. “Composer with a Conscience: Elie Siegmeister in Profile,” American Music 6, no. 2 (1988): 158–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/3051547. The 1935 Broeklundian notes, “Mr. Siegmeister;’s great ability to correlate social conditions with music.” See 1935 Broeklundian, 117, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

2 “Negro and War Is Topic of Discussion,” Spotlight 27 April 1934, 3; “Forum Undertakes Defense of Negros,” Spotlight 2 November 1934, 1; “Air Negro Problem at Club Symposium,” Spotlight 16 March 1934, 1; For information on Richard B. Moore see Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression (New York: Grove Press, 1984), 3-25. “Air Negro Problem at Club Symposium,” Spotlight 16 March 1934, 1.

3 Naison, 75. For more on Herndon, see Edward Hatfield, “Angelo Herndon Case.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Aug 3, 2020. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/angelo-herndon-case/

4 “Forum Undertakes Defense of Negros,” Spotlight 2 November1934,1; “Clubs,” Pioneer 21 Nov 1934, 7: “Rally for Scottsboro Defendants Sponsored by Negro Study Forum,” Pioneer 12 December 1934, 2.

5 “Removal of Electric Chair Petition Halts Scottsboro Campaign,” Pioneer 19 December 1934, 3

6“Removal of Electric Chair Petition Halts Scottsboro Campaign,” Pioneer 19 December 1934, 3; “Electric Chair Languishes Pending Action,” Spotlight 14 December, 1934,1: “Council Sanctions Spectacular Chair,” Spotlight 21 December 1934, 1.

7 “Urge Students’ Aid in Scottsboro Case,” Spotlight 14 December 1934, 3.

8 “Negro and White Students Hit Italy’s Invasion of Ethiopia,” Pioneer 23 October 1935, 1.

9 “Club Notes,” Beacon 14 October 1935, p3. “Club Notes,” Beacon 25 March 1935,4; “Club Notes,” 11 April 1935, 4; “Negro Club Makes Delinquency Study,” Beacon 23 November 1936; “Nite Clubs,” Beacon 28 September 1936, 4. There is very little information on the Negro Problems Club in the Archives. The Club is first mentioned in the Beacon in March 1935, and a subsequent article gives some evidence that the Club began that year. Also, since the Beacon is the primary source of information on the Club, the archival record is silent after the Beacon ceased publication in February 1942. There was no evening newspaper until 1947 when publication of the Ken began. An article in November 1948 lists the NAACP as a club. There is no mention of the Negro Problems Club. See “New Clubs Being Organized,” Ken 15 November 1948,1.

10 “Nite Clubs,” Beacon 4 May 1936, 5; “Nite Clubs,” Beacon 30 November 1936, 3; “Nite Clubs,” Beacon 14 December 1936, 3; “Negro Problems Club Joins Youth Groups,” Beacon 4, March 1940, 1; “Negro Club Makes Delinquency Study,” Beacon 23 November 1936,1. The American Youth Congress, founded in 1934, was a coalition of student, labor, religious, and civil rights groups that lobbied for legislation and federal aid. See Robert Cohen, When the Old Left was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement, 1921-1941 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 189-195. The Brooklyn Youth Federation was affiliated with the National Negro Congress. See “Browsing Brooklyn: Before the Snow Hi Y’All” The New York Amsterdam News 12 December 1936, 12.

11 “Negro Club Favors Anti-Lynching Bill,” Beacon 6 May 1937, 1; “Back Anti-Lynch Bill: Support Urged by Negro Group,” Beacon 29 November 1937, 3. “Nite Club” Beacon 28 September 36, 4; “Negro Club Makes Delinquency Study,” Beacon 23 November 1936,1. For more information on the anti-lynching bill, see “Costigan Wagner Bill,” NAACP.org, accessed on 8/21/22 https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/legislative-milestones/costigan-wagner-bill.

12 “Dr. Abel lectures on Negro Problems,” The New York Amsterdam News 5 December 1936, 23; “Club Chatter,” Vanguard 26 February 1937, 6. Dollie Lowther Robinson attended BC from 1934-1942 and in 1971.

13 Dorothy Sue Cobble, “Halving the Double Day,” New Labor Forum 12, no. 3 (2003), 65.

14 “Miss Dollie Robinson Joins Local 144 as Aide to Ottley,” New Pittsburg Courier, 8 June 1963, 3; “Who’s Who in the Upcoming Primary Elections on June 18,” New York Amsterdam News 8 June 1968, 25.

15 “Mrs. Robinson Quits DC Post; Joins 144,” New York Amsterdam News 8 June 1963, 7.

16 A Hammer in Their Hands: A Documentary History of Technology and the African-American Experience, edited by Carroll Pursell, MIT Press, 2005. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/brooklyn-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3338480.

Created from brooklyn-ebooks on 2022-07-02 15:07:24; “Muriel E. Baldwin,” J. Foster Phillips Funeral Home, accessed on 7/30/22, https://www.jfosterphillips.com/obituary/1251788.

17 “National Campaign on to Open More Phone Jobs,” The New York Amsterdam News, 2 February 1946, 5; “Commission Finds Less Bias in Jobs,” New York Times 9 July 1946, 20. “Muriel E. Baldwin” J. Foster Phillips Funeral Home, accessed on 7/30/22, https://www.jfosterphillips.com/obituary/1251788.

18 “Muriel Robinson Baldwin ’40,” Brooklyn College Office of Alumni Engagement.

19 “Cagers Win Intersectional Contest over All Negro Hampton Five, 46-31,” Vanguard 28 January 1938, 4; “Hampton Quintet Bows to Brooklyn Team,” The New York Amsterdam News 29 January 1938, 17.

20 “All-Negro Cast Dramatizers Varsity’s ‘Abraham’s Bosom,’” Vanguard 2 December 1938, 1. Note: All but two cast members were African Americans.

21 “Groups Rescind Negro Exclusion from House Plans,” Vanguard 21 November 1939; “House Plan Fight Bar on Negros,” Vanguard 15 December 1939, 1; “Attacks House Plan Stand on Negro Study Forum,” Vanguard 15 December 1939, 2; “Negro Discrimination Blight on Campus,” Vanguard 21 December 1939, 2.