Flyer distributed by the Harriet Tubman Society, March 1942. Handbill Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

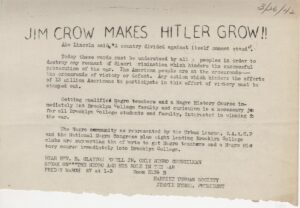

During WWII, African American students mounted several civil rights campaigns on campus. Students held meetings and rallies, bringing attention to segregation in the US military, unfair labor practices at the municipal colleges, and the lack of an African American history class at Brooklyn College. Often receiving support from the student newspaper and other Brooklyn College clubs, African American students highlighted the gap between US war rhetoric and reality. Even though the archival record consists of only a few flyers and clippings from student newspapers, the documents show that these students were well-organized, motivated, and held events featuring prominent African American politicians and activists.

The level of activism during the war can be traced to the rise of national student movements during the 1930s, with the Great Depression serving as a catalyst. Students disillusioned by unemployment, retrenchment, and the lack of academic freedom began to question American society and called for a more equitable future. Two left-leaning national student organizations, the National Student League (NSL) and its successor, the American Student Union (ASU), emerged and soon dominated campus protests. At the same time, this era also saw the growth of the NAACP’s college chapters.1 According to historian Robert Cohen, the student movement of the 1930s “demonstrated a concern with both the new inequities created by the Depression and the old inequities perpetuated by racism…They envisioned an academic community and a nation free of racial prejudice and discrimination. Depression-era student activists raised the banner of racial equality on more campuses than any other previous generation of students in twentieth-century America.”2

While there are examples of NAACP activism on campus,3 most of the documents found in the Brooklyn College Archives are those produced by communist and left-leaning groups. Concerned about communist activity, the College administration, particularly under President Harry Gideonse, kept a close eye on both faculty and student organizations believed to be affiliated with the Communist Party or espousing similar political views. This monitoring included collecting campus flyers and leaflets viewed as subversive. Of particular interest were the activities of the ASU and the Young Communist League, along with clubs and student publications that formed alliances with them, including the Beacon, the Vanguard, the Karl Marx Society, the Student Party, and the Negro Study Forum.

Following a resolution at the 6th Comintern in 1928, the Communist Party in America began to focus on racial and economic issues affecting African Americans, now recognized as an essential part of the revolutionary movement. After this policy change, advanced by African American communists and agreeable to the strategic needs of Moscow, US communists worked for racial equality in both the north and the south, recruited African Americans, staged protests, and mounted legal defense for those wrongly accused of crimes.4

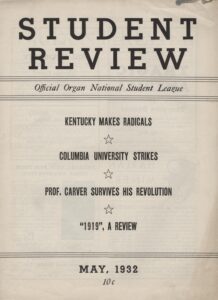

The May 1932 issue of the Student Review contains the program of the NSL. Brooklyn College Archives.

The importance of African Americans to the student movement is evident in the program of the National Student League (NSL). Brooklyn College was one of the seven original member institutions of the NSL started by communist students at CCNY in 1931.5 The NSL’s program, published in their magazine, the Student Review, detailed their philosophy and goals, including academic freedom, workers’ rights, and an end to capitalism, fascism, and imperialism, with the Soviet Union as “an inspiration and guide.”6 African Americans are mentioned throughout the document. The preamble stated that democracy under capitalism is a myth:

Especially is the myth of ‘democracy,’ and civil liberty exposed in the system of Jim Crowism, segregation, and lynch law. The ruthless use by the governing class of the principle of ‘divide and rule’ is the greatest single obstacle to the success of the Negro and white students in their common struggle. The Negro students, in addition to bearing the brunt of race discrimination, also find themselves in an economic position even worse than that of the white student. Only by working side by side on the basis of full social and political equality can the Negro and white student build a strong militant movement.7

The second of the NSL’s 12 student demands called for an end to discrimination in college admission requirements and the use of college facilities. It stated, “We demand that Negros shall have the right to enter freely, and on equal terms with white students, all colleges and universities in the country.”8

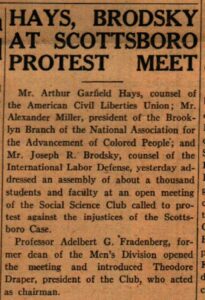

Subsequent issues of the Student Review contained articles on the plight of African Americans in colleges across the country and on the Scottsboro case, in which nine African Americans were wrongly convicted of rape and sentenced to death. NSL members attended the trials and held “Scottsboro Weeks” on college campuses.9 In May 1933, the Brooklyn College Social Sciences Club held a Scottsboro protest meeting attended by 1000 students and faculty. Undergraduate Theodore Draper, the club’s president, and staunch NSLer, moderated the event. Draper, who would become an eminent historian known for his scholarship on the American Communist Party, was asked by the NSL to transfer from City to Brooklyn to increase their influence at BC.10 Speakers at the meeting included noted ACLU lawyer Arthur Garfield Hays, Alexander Miller, president of the Brooklyn branch of the NAACP, and Joseph Brodsky, general counsel for the International Labor Defense (ILD).11 As the legal arm of the Communist Party, the ILD was the first group to represent the Scottsboro defendants, leading to years of battling between the NAACP and the ILD for control of the case.12

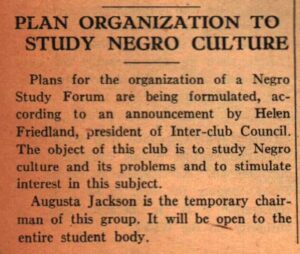

Clipping from the Spotlight, November 1, 1933. Brooklyn College Archives.

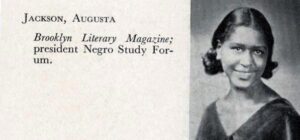

The first mention of an African American club on campus appears in the November 10, 1933 edition of the Spotlight, Brooklyn College’s Women’s Division newspaper. In that issue, it was announced that plans were underway to form a Negro Study Forum whose objective was “to study Negro Culture and its problems and to stimulate interest in this subject.”13 Augusta Jackson ’34 became president of the Forum and the only African American to serve on the staff of the College’s Brooklyn Literary Magazine.14

After graduation, Jackson played a pivotal role in the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC). Although not all members were communists, the SNYC was an outgrowth of the communist-inspired National Negro Congress (NNC). SNYC members were “the shock troops of struggles for black equality in the Jim Crow South during the war.”15 In 1938, Jackson married fellow communist Edward Strong, a student activist and ASU leader who was one of the founding members of the SNYC. In 1939 they moved to Birmingham, Alabama, the SNYC’s new headquarters.16 There, she was part of a core of SNYC women, including fellow BC alum Dorothy Challenor Burnham ’36, who held leadership positions and pushed for an end to sexism within the Birmingham CP. In his book, Sojourning for Freedom, Erik S. McDuffie wrote, “Black left organizations such as the SNYC and the NNC were unique at this historical moment in their promotion of black women as titular heads of secular, mixed-gender black protest organizations.”17

While working at the SNYC, Jackson taught at Miles College and edited the SNYC’s short-lived magazine Cavalcade: The March of the Southern Negro. Jackson’s poem “The People to Lincoln, Douglass” appeared in one issue. According to historian Robin Kelly, Jackson’s poem showed “similarities between poor whites and blacks as well as the forms of oppression unique to the black experience, hearkening back to the CP in the early 1930s. The entire poem subtly suggests a future, interracial, working-class movement that would incorporate some form of black self-determination.”18 As members of the Communist Party, Jackson’s family, like the Burnhams, were under FBI surveillance, particularly during the McCarthy era. Augusta Jackson burned letters out of fear that the government would raid the family home, while Dorothy Burnham’s daughter recalls being terrified after the Rosenbergs were executed in 1953.19 In 1964, Jackson wrote that the civil rights issues currently on the national stage were first championed by the SNYC: “For a dozen years the youth had carried the baton in this fateful race, they had influenced the perspective of a generation of southerners. Now they handed the baton on to the Negro people as a whole.”20

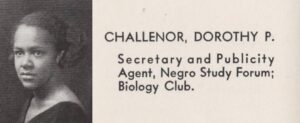

Dorothy Challenor Burnham, a microbiology major and a member of the Negro Study Forum who joined the Communist Party in 1936, recalled meeting Brooklyn College professors interested in the civil rights movement. After graduation, she could not find employment in her field and moved to Birmingham in 1942 with her husband, one of the SNYC founders, Louis Burnham. Louis, a CCNY graduate and fellow communist, headed his college’s Frederick Douglas Society and was picked by the ASU to organize chapters at Historically Black Colleges and Universities.21

Dorothy Burnham worked as the educational director for the SNYC and handed out leaflets to coal and steel workers to educate them about equal pay for equal work.22 In 1946, Burnham was a delegate to the World Federation of Democratic Youth and a member of several civil rights organizations, including Women for Economic and Racial Equality, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and the Sisters Against South African Apartheid. She, like Jackson, wrote for Freedomways during the 1960s.23 Burnham eventually found a job in her field teaching biology at Hostos Community College and Empire State College.24

After being established as a club in the men’s and women’s divisions, the Brooklyn College Negro Study Forum championed African American issues on campus and often partnered with other student groups in anti-war strikes.25 Although Brooklyn College did not keep statistics on the number of African American students, the total was relatively small. In 1933, The Crisis published statistics on the number of African Americans at majority white colleges. While Brooklyn College is not mentioned, 204 African Americans were enrolled at Hunter College (3rd on a list of 64 schools), and 73 enrolled at City.26 Brooklyn College, founded in 1930 after the combination of the Brooklyn branches of City and Hunter, had in 1933 an enrollment of less than half that of its parent institutions.27 A June 1933 article from The Amsterdam News lists seven African American Brooklynites who graduated from BC that spring.28 US Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm ‘46 recalled in her autobiography that there were only about 60 African American students during her time on campus.29 Though small in number, many of these Brooklyn College African American activists like Jackson, Burnham, and Chisholm would, after graduation, play a prominent role in the civil rights movement.

Endnotes

1 See Thomas L. Bynum, ” ‘We must March Forward’: Juanita Jackson and the Origins of the N.A.A.C.P. Youth Movement,” The Journal of African American History 94, no.4 (fall 2009): 487-508.

2 Robert Cohen, When the Old Left was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement, 1921-1941 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 204-205.

3 For an example, see flyer “Open on all Fronts” Box 748, Folder 11, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

4 For more information on the Communist Party and the Negro Question, see J.A. Zumoff. “The American Communist Party and the ‘Negro Question’ from the Founding of the Party to the Fourth Congress of the Communist International” Journal for the Study of Radicalism 6, no. 3 (Fall 2012), 53-89; Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression (New York: Grove Press, 1984), 3-30; Theodore Draper, American Communism and Soviet Russia (New York: Vintage Books, 1986), 315-356.

5 Cohen, 28-31.

6 “Program of the National Student League,” Student Review 1, no.4 (May 1932): 17.

7 “Program of the National Student League,” Student Review 1, no.4 (May 1932): 16.

8 “Program of the National Student League,” Student Review 1, no.4 (May 1932): 17.

9 For more information on the Scottsboro Case, see James R. Acker, Scottsboro and Its Legacy: The Cases That Challenged American Legal and Social Justice (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007); Naison, 57-89; Cohen, 211. Examples of articles in the Student Review (note: not exhaustive): “The Negro in College,” Student Review II, no.4 (February 1933): 9; “From Scottsboro to Decatur,” Student Review II, no. 6 (April 1933): 12-13; “No More Tea Parties,” Student Review II, no.6 (April 1933): 15; “Bourbon Rule in the Black Belt,” Student Review II, no.6 (April 1933): 17-18; “Scottsboro a Challenge,” Student Review II, no. 7 (May 1933): 11; “A Guide to Action: Proposed Resolutions of Student Conference on Negro Student Problems,” Student Review II, no. 7 (May 1933): 19-20; “Negro Students Act,” Student Review III, no. 4 (April 1934): 5-6; “Inciting to Riot,” Student Review V, no.1 (October 1935): 9.

10 “Hays, Brodsky at Scottsboro Protest Meeting,” Spotlight 18 May 1933, 1; “Hays to Discuss Scottsboro Case at Meeting Today,” Pioneer 17 May 1933: 1; Draper, ix-x.

11 “Hays, Brodsky at Scottsboro Protest Meeting,” Spotlight 18 May 1933, 1.

12 Naison, 57-89. See also William F. Pinar, “The Communist Party/N.A.A.C.P. Rivalry in the Trials of the Scottsboro Nine,” Counterpoints, Vol 163 (2001): 753-811.

13 “Plan Organization to Study Negro Culture,” Spotlight 10 November 1933, 3.

14 In the May 1933 issue of the Brooklyn Literary Magazine, Augusta Jackson’s short story, “Zelia: Another Life,” about a biracial southern woman’s conflicts with her family and struggle to find her place in the world, appears. See “Zelia: Another Life,” Brooklyn Literary Magazine (May 1933): 27-33, Brooklyn College Archive and Special Collections. Jackson also wrote for the Crisis: “A New Deal for Tobacco Workers,” Crisis 46, no. 10 (October 1938): 322-324; “Youth Meets in Birmingham,” Crisis 46, no.6 (June 1939): 178.

15 Erik S. McDuffie, Sojourning for Freedom: Black Women, American Communism, and the Making of Black Left Feminism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 141; Cohen, 220-224. Conceived by Communists, the National Negro Congress (NNC), founded in 1935, was an alliance of communist and non-communist African American groups and intellectuals formed to fight racial discrimination and fascism and to advocate for workers’ rights. Marion Cuthbert, the first African American professor hired at Brooklyn College, was elected secretary at the NNC’s first convention. In 1946, the NNC, the ILD, and the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties merged to form the Civil Rights Congress. The Southern Negro Youth Congress, founded in 1936, was an outgrowth of the NNC’s youth councils. See Naison, 177-184; Kelley, 200-219; and Cohen, 220-225. ASU support for the NNC was reported in the Beacon. See “National Negro Congress O’ked by Student Union,” Beacon February 10, 1936, 2. In 1937, The Vanguard reported that the Negro Study Forum “is affiliated with the Brooklyn Youth Federation of the National Negro Congress, whose purpose is to bring about a closer union of the clubs in Brooklyn and to further the aims of the Negro through united action.” See “Club Chatter,” Vanguard 26 February 1937, 6.

16 Robin D. G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression (Chapel Hill, U of North Carolina Press, 1990), 204.

17 McDuffie, 145. See also McDuffie,141-151 and Kelley, 205-207.

18 Kelley, 211.

19 McDuffie, 186 – 188. Augusta Jackson’s papers can be found within her husband’s collection at Howard University: https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1184&context=finaid_manu

20 Augusta Jackson Strong, “Southern Youth’s Proud Heritage,” Freedomways: A Quarterly Journal of the Negro Freedom Movement 4, no. 1 (Winter 1964): 50.

21 McDuffie, 98; Kelley, 222; Cohen, 219; John Rich, Dorothy Burnham “Excerpts” Vimeo, accessed on 7/30/22, https://vimeo.com/118977130.

22 John Rich, Dorothy Burnham “Excerpts,” Vimeo, accessed on 7/30/22 https://vimeo.com/118977130

23 “Dorothy Burnham Civil Rights Activist,” accessed on 7/30/22, https://www.cpusa.org/article/dorothy-burnham-civil-rights-activist/; John Rich, Dorothy Burnham “Excerpts,” Vimeo, accessed on 7/30/22 https://vimeo.com/118977130; For more on Freedomways see Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists During the Cold War (New York: New York University Press, 2011),135-140. Burnham’s articles for Freedomways include (note: not exhaustive) “Jensenism: The New Pseudoscience of Racism,” Freedomways 11, no.2 (1971): 150-157; “Science on Racism,” Freedomways 15, no. 2 (1975):89-95; “Biology and Gender: False Theories About Women and Blacks,” Freedomways 17, no. 1 (1977): 8-15; “Children of the Slave Community in the United States,” Freedomways 19, no. 2 (1979): 75-81.

24 “Sen. Montgomery Honors ‘Renaissance Woman’ Burnham with Lifetime Achievement Award,” Brooklyn Eagle (edit@brooklyneagle.net), published online 07-13-2011)

25 “Anti-war Conference at B.C.,” Pioneer 13 December 1933, 1; “Negro and White Students hit Italy’s Invasion of Ethiopia,” Pioneer 23 October 1935.

26 “The American Negro in College 1932-1933,” The Crisis 40, no. 8 (August 1933): 181.

27 See Minutes of the Board of Higher Education March, May, and November 1932. Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

28 “They’re Graduates,” New York Amsterdam News 21 June 1933, 11a. In this article, the following people are listed as Brooklyn College graduates: Vivian Belk, Kathleen George, Bernice I. Hicks, Minerva Critchlow, Samuel “Gus” Walker, Gladys Edgehill, and Lucille Cromer (teacher’s certificate).

29 Shirley Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 22.