During WWII, many rural areas in the United States faced a shortage of agricultural workers. As men entered the armed forces or left the countryside for higher-paying jobs in war-related industries, temporary workers were needed to fill the gap. Brooklyn College President Harry Gideonse viewed this as an opportunity to put into practice his philosophy of an “other-than-intellectual” educational experience for undergraduate students. While the wartime labor shortages led to the creation of the Farm Labor Project, Gideonse hoped that this program would continue after the war and become a permanent part of the curriculum.

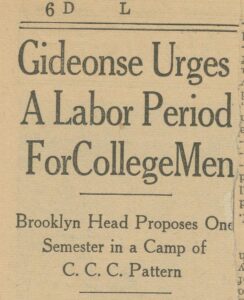

Clipping from a local newspaper about Gideonse’s plan for student work camps. Farm Labor Project, Brooklyn College Archives.

Gideonse described his plan in his annual reports to the Board of Higher Education, in academic publications, and during a radio broadcast, bringing his message directly into the homes of New Yorkers. According to Gideonse, the hands-on education once received by the children of the Puritan and Calvinist colonists as they built barns, plowed fields, tended to livestock, weaved, and cooked had generated an appreciation for labor and collaboration. At the same time, their shared experiences had provided a foundation for American democracy. In his radio broadcast, Gideonse stated that the qualities of free men—teamwork, shared values, leadership, and “intelligent followship”—“developed out of our family, religious, and frontier life. Today we shall have to build an educational program to develop such qualities…In that sense, educational reconstruction is as vital to freedom as the military struggle itself.”1

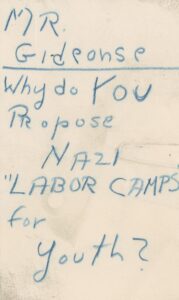

An unsigned postcard sent to President Gideonse. Farm Labor Project Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

Gideonse’s plan to put students to work on farms drew criticism from both the left and the right, forcing him and other educators to present detailed histories of post-WWI student work camps in order to dissociate the programs in America from those in Nazi Germany.2 Gideonse wrote of the Farm Labor Project: “On the left, it was promptly labeled as ‘fascist’ because the Nazis have used such camps to achieve their own purposes…On the right, the suggestion was promptly smeared with the label ‘communist’ apparently on the ground that it carried an aroma of New Deal methods.”3

Opposition from the left was particularly vocal, especially from the American Student Union (ASU), which had a branch on the BC campus. While the ASU agreed with Gideonse that college education “tends too much toward ivory-towerism,” for them the solution was not to be found in compulsory labor camps. Instead, the ASU called for higher wages for young people, including students participating in New Deal Programs: “Forced-labor-camps was Hitler’s way out. Shackling American youth to permanent insecurity, low wages, and denial of civil rights, it will create a huge army of cheap labor with which to undermine the economic standards fought for by the American labor movement. Brutalizing and militarizing American youth, it will create a machine in itself destructive of youth’s democratic aspirations and take giant strides toward lining up American youth for entrance into war.”4

Professor Benedict registering a student for the Farm Labor Project, circa 1942. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

Despite opposition, Brooklyn College instituted its Farm Labor Project in 1942. Gideonse placed Biology Professor Ralph Benedict in charge. While teaching at Bushwick High School during WWI, Benedict had supervised students sent to Long Island to aid in wartime food production. Approximately 200 New York City high school boys from schools across the city had participated in the WWI project, working in the fields from May until October. 5

During the summer of 1942, 67 Brooklyn College undergraduates and students from 19 other New York colleges participated in NY State’s Farm Cadet Victory Corps. Most of the 100 undergraduates involved were assigned to three camps in Dutchess County, NY: Calvert Camp in Germantown; Kleisrath Camp near Red Hook; and the largest group consisting of 40 men and 24 women at the Red Hook Camp in Red Hook, NY.6

A BC student picking cherries, 1942. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

While upstate, Brooklyn College students harvested fruits and vegetables, including 40,000 quarts of strawberries.7 Gideonse stated, “The work was too tough for some of our city-bred students, but an overwhelming majority stuck to it with admirable endurance. They were all volunteers and they were doing it in spite of a very small economic return—much smaller than the amount they could earn in town during the summer months. Theirs was a patriotic response to public necessity—and that, of course, is splendid. But I confess, I was personally interested in it as a trial of a possibly vital and permanent educational idea.” 8

In his report to President Gideonse, Professor Benedict proposed that future summer projects should contain an educational component so that the students could take classes and earn credits toward graduation while volunteering. After student lodging in historic homes proved less than ideal, Benedict also proposed that the College, not the government, find placement for the students and manage the project.9 Gideonse agreed, and after eight months of planning, 150 BC undergraduates and 8 faculty members participated in the 1943 Farm Labor Project in Morrisville, New York.

Farm Labor Project orientation near current-day Hillel Place, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

BC students sitting on the lawn of the Morrisville Institute, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

That summer, students picked peas and beans on farms owned by Grove M. Hinman. Female students stayed at the dormitory of the New York State Agricultural and Technical Institute in Morrisville, while the men stayed in local homes. Since no classes were held at the Institute during the summer, the classrooms, cafeteria, gym, and assembly halls were available for use.10

The student volunteers paid the same library and textbook fees as they did at the Midwood campus. In addition, students were charged $2.00 per week for room and board and $5.00 a week for a cafeteria meal ticket. Students were also required to pay $2.75 for accident insurance. Ideally, the money to cover their expenses would come from their labor in the fields. Hinman paid the students 40 cents per bushel of peas picked and 45 cents per bushel of beans. According to an official BC pamphlet, 6 to 10 bushels “constitute a fair day’s picking.”11

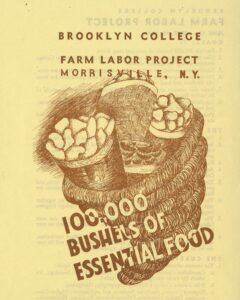

Cover of a 1943 BC Pamphlet urging students to sign up to “Feed a Fighter in ’43.” Farm Labor Project Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

However, weather, crop quality, and the skill and stamina of the students affected the number of bushels picked. Excessive rain during the spring delayed the planting of crops forcing BC to postpone the start of the project. Frequent summer rainstorms also prevented students from working in the fields, while root blight resulted in a smaller yield. What was planned as a 12-week program turned out to be only 10 weeks, and the students picked 22,000 bushels, far below the College’s goal of 100,000. Yet, the BC program was the most successful of the thirty camps in NY State’s Farm Cadet Victory Corps and the only one to have an educational component.12

As an incentive to pick more bushels, Hollywood actor and Brooklynite Edward Everett Horton donated $150.00 in prize money to be awarded to each week’s best picker. At first, the prize was $5.00 at the end of each week for the student who picked the most bushels but was then changed to $2.00 for the five students with the highest weekly totals, with the previous winners ineligible. 13

The Horton prizes were given out at Friday night assemblies, where students listened to lectures related to agriculture and speeches from local leaders. Classes were held two evenings per week, with labs on a third evening.14 Courses in English, Geology, Farm Biology, and Political Science were offered, and upperclassmen had the option of taking Rural Sociology.15 Institute staff taught students the fundamentals of tillage, plowing, and pasteurization. Classes such as Geology included field trips. Depending on the needs in the fields, students worked up to six days per week. Free time was limited.16

BC students learning about the pasteurization of milk, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Library.

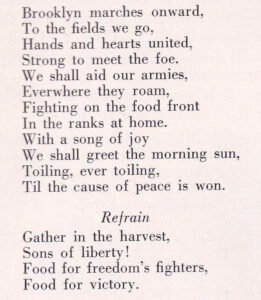

The official marching song of the Farm Labor Project. Farm Labor Project Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

A silent film and approximately 200 photographs documenting the summer’s activities helped to publicize the project and were used as a recruitment tool for the summer of 1944.17 Additionally, Dr. Alfred G. Walton of the Flatbush Congregational Church, of which Professor Benedict was a member, wrote the lyrics for the project’s marching song sung to the tune of the Harrow song “Forty Years On.”18

The third and last Farm Labor Project took place in Morrisville during the summer of 1944. Despite an aggressive recruiting campaign, only 125 students participated, including 25 from 1943 who “re-enlisted,” harvesting a total of 16,000 bushels.19 Additional courses in Hygiene (physical education) and First Aid were offered, along with Military Topography (Geology 7) and Navigation.20 As in 1943, the planning committee wanted to offer a wide variety of courses tied to the rural setting and the war effort. However, the College had difficulty securing professors who could relocate to Morrisville for the summer and were also willing to take on supervisory and administrative functions. Aside from their classroom responsibilities, faculty were assigned to supervise the students in the dorms and in the fields during the long workdays.21

A BC student picking peas, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

During the summer of 1944, Benedict sent periodic reports to President Gideonse, revealing the difficulties he faced administering the project. “This particular staff member,” Benedict wrote, “feels his deficiencies, due to age, and insufficient energy, and this summer has seen more than usual complications.”22 While acknowledging the project’s value for both the students and the nation, he worried about the future recruitment of adequate staff and students and the management of student facilities: “Questions arise, however, as to the practicality of the program, given the present basis. Can we hope to work it out with our Brooklyn group of students, even during the war, considering all that it requires in the way of staff service and hours and moderate remuneration? Can we get a better student group? Can we hope to demonstrate the potentialities of a permanent program? Can we hope year after year to enlist appropriate staff?”23

After a long and hot summer studded with student unrest, Benedict proposed a revamped Farm Labor Project with far fewer students and a balance between farm work and classes.24 When the College learned that they needed to hire a cafeteria manager for the summer of 1945, the project was halted due to cost. The manager’s salary would have been added to student fees, which would have been impossible for the students to afford considering the small amount they earned per bushel. Lack of proper housing for faculty with families in Morrisville was also an issue, along with no funds to replace and repair BC equipment brought upstate during the previous summers.25

After the war ended, the College did not revive the Farm Labor Project. In the post-war years, the College administration concentrated on the needs of returning veterans and the improvement and expansion of the curriculum. Gideonse also focused on getting funds for a much-needed auditorium and student center. Still, despite only lasting three years, the Farm Labor Project was an integral part of BC’s war effort and a direct application of Gideonse’s academic philosophy.

President Gideonse watching the students pick beans, Morrisville, 1943. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.