At the 25th Anniversary luncheon, Gideonse confers the Brooklyn College Medal of Honor on John Hope Franklyn, Chair of the History Department. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

On May 9, 1964, Brooklyn College held a luncheon in honor of Harry D. Gideonse’s 25th anniversary as President. There was much to celebrate. During Gideonse’s tenure, Brooklyn College became nationally recognized for its academic excellence. The College could boast a top-notch faculty, an expanded curriculum, and an increase in the number and quality of both academic programs and student services. Yet, Gideonse remains one of the most controversial and divisive figures in the College’s history. He is either lauded as a hero and great educator in hagiographic accounts, found in such books as A City College in Action, or decried by faculty and alumni as an autocrat who stifled academic freedom and students’ rights.1

During his first decade as President, Gideonse laid the framework for his vision of modern higher education, one in which the faculty, the curriculum, and student programs worked in conjunction to produce a well-rounded student who would be immune to the siren song of Communist ideology. While putting his plan into action, Gideonse clashed with the faculty, the students, and the Board of Higher Education. Through it all, he remained steadfast in the righteousness of his position. As one alumna succinctly put it, “poppa knows best.”2

Harry Gideonse was born in Rotterdam, Holland in 1901. Gideonse’s father, who worked for the Vacuum Oil Company (now part of Exxon Mobil), was transferred to the United States in 1904. The family returned to the Netherlands in 1911, but the Great War would drastically change the family’s financial situation. During WWI, his father sold petroleum products to the Germans and went bankrupt after the Allies confiscated his stockpile of paraffin meant for the Central Powers. With his father unable to pay for his college education, Gideonse returned to America, working briefly as a translator for Eastman Kodak. He then moved to New York City and attended Columbia University, earning his undergraduate and master’s degrees in Economics. In 1926, he received a Diplôme des Hautes Études from the University of Geneva. Before becoming President of Brooklyn College, he taught at Columbia, Barnard, Rutgers, and the University of Chicago. 3

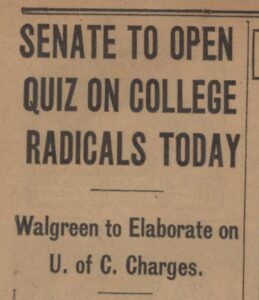

While teaching in Chicago, Gideonse’s critique of the University President’s proposed curriculum changes and his testimony in a state investigation of Communist activity brought him into the national spotlight. The niece of drug store magnate Charles Walgreen wrongfully accused Gideonse and another professor of being Communists. They were eventually cleared of all charges.4 When the Board of Higher Education chose Gideonse to be BC’s second President in 1939, “many of the faculty anticipated a liberal president who understood what it meant to serve under an authoritarian.”5 As we shall see in future posts, some professors, including Jessie Clarkson and Joseph Cohen, had reason to regret their initial support.

Before accepting the position, Gideonse requested changes to the Board of Higher Education’s Bylaws. Initially, the Board refused, but after Gideonse threatened to withdraw his name from consideration, the Board relented and made two alterations. First, College Presidents would now have the power to appoint deans; and second, when faculty elected a department chairperson, it would be considered a nomination and not a binding decision. If a President disagreed with the election results, he could nominate another faculty member, and the two names would be sent to the Board for a final verdict.6

Gideonse wasted no time in using his newfound power. Before even setting foot on campus, he appointed an outsider, Robert Bridgman, to be the first Dean of Students. His decision not to choose a member of the BC staff irritated the faculty, who also believed that Gideonse should have consulted them. Faculty petitioned the Board, arguing that Gideonse needed to become more familiar with the College before hiring a dean. Not wanting to lose Gideonse, the Board placated the faculty and endorsed Bridgman’s appointment. In a terse letter to Board Chair Ordway Tead, Gideonse stressed that student life and the College’s relationship with the community was in such a dire state that he needed to act immediately and appoint a competent dean who shared his educational philosophy. He wrote, “I shall certainly not need six months at Brooklyn College to confirm one impression that stands out like a pikestaff. It is the social or emotional poverty of the total situation in which the city college students find themselves…A vigorous program toward implementation of the social and other-than-intellectual needs stands very near at the top of my agenda.”7

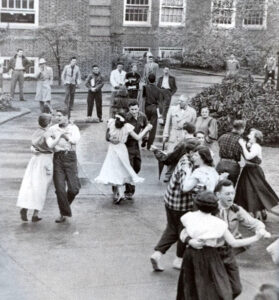

BC’s annual Country Fair had all the proper extra-curricular elements: square dancing, carnival games, theatrical skits, and a king and queen crowned by Gideonse himself. An array of student committees started planning the May event during the fall semester. Brooklyn College Photographic Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

In his Inaugural Address, Gideonse detailed his concept of the “other-than-intellectual needs” of the undergraduate student. Due to the decline in the influence of the church and family, a college, Gideonse argued, can no longer provide an education based solely on objectivity and subject competence but must also teach the ethics and morality necessary to maintain a free society. Student guidance programs and extra-curricular activities should not be considered “fads and frills” but an integral part of the curriculum. Gideonse gave as an example the success the Scandinavians had in educating the “whole man.” These countries put emphasis on the “social and cooperative aspects of education, on folk song and folk dance, on the role of tradition, myth, and religious observance, and on the peculiar educational fruits of working together.”8 If academia did not adapt, then the void would be filled by popular culture and totalitarian regimes. Teaching morality, not acquiring material goods or a rise in the standard of living, was the answer. He argued that “Talent and funds formerly restricted to academic purposes in the narrow sense of the term must now be shifted from sheer cultivation of intellectual virtues to education for the whole man.”9

And shift talent and funds he did. Dean Bridgeman created a Personnel Bureau to provide counseling and guidance for students, while Gideonse pushed for committees to oversee student activities. These committees drafted a series of airtight regulations, which Gideonse hoped would loosen the grip he believed the Communist minority held over student activities and the student press. For Gideonse, this labyrinth of rules would rid the College of the Communist menace and repair the damage to the BC’s reputation caused by years of leftist activity.

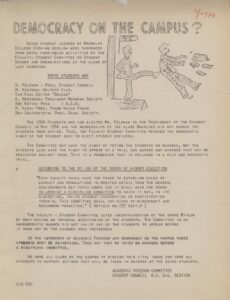

On January 6, 1941, the Faculty-Student Committee suspended seven Evening Session students. Handbills critical of this move flooded the campus. The Student Council’s Academic Freedom Committee submitted a report to the ACLU and the Board charging that the “Faculty-Student Committee is attempting to coerce and intimidate student groups and organizations which do not agree with and fall into step with President Gideonse’s policy.” 11

Almost immediately, the Faculty-Student Committee on Student Groups and Organizations began to clamp down on clubs, newspapers, and left-leaning undergraduates. For example, to prevent Earl Browder from appearing at a 1939 meeting of the Karl Marx Society, the Committee enforced a newly created rule forbidding anyone under indictment to speak on campus. In 1941, they suspended the Beacon newspaper for failing to submit its budget and the names of its editors by the appointed deadline. That same year, seven Evening Session students were suspended for signing leaflets and attempting to hold what the Committee defined as an “unauthorized” meeting. 10 Punishing the violators of trivial rules continued throughout the Gideonse administration, culminating in revoking the Vanguard newspaper’s charter in 1950.

In October 1940, statements about academic freedom made by Nicolas Butler, the President of Columbia University, set off a firestorm of criticism from faculty and students alike, even at Brooklyn College.12 While the majority of his remarks referred to the activities of faculty outside of the classroom, he also added that academic freedom applied only to faculty and not to students. Gideonse, in a statement to the Vanguard student newspaper, agreed with Butler’s assessment of student rights:

“The words ‘academic freedom’ are simply an English translation of the German Lehrfreiheit, that is to say, freedom to teach. Since students do not teach but are taught, that is a matter that concerns students only so far as they are the principal beneficiaries of a free faculty, or the principal victims of a gagged faculty. In the United States individual institutions have frequently extended the idea of academic freedom to students as a matter of institutional or faculty policy…It is an educational experiment, and its results will be judged by the conduct of the groups and individuals that exercise that privilege. It is definitely not part of the historic tradition of academic freedom itself.”13

Butler and Gideonse were not the only ones who shared these views. In his book When the Old Left was Young, Robert Cohen states that many college presidents in this era viewed students as “immature youths in need of discipline and guidance rather than as adults with constitutional rights. College administrators believed that students lacked intellectual maturity and were therefore ripe for exploitation and manipulation by cynical radical organizations…For them suppression of radicalism on campus was equated not with the authoritarianism of a harsh dictator, but the firm hand of a concerned parent.”14 He added, “Courts consistently enforced the traditional in loco parentis doctrine ruling that the college administrator and teachers’ stand in place of the parent…with the same power to control and punish.”15

But unlike other college administrators, Gideonse would go one step further, arguing that the college replaced both the family and the church. In his Annual Report of the President for the Years 1940-1941, Gideonse bluntly stated, “It remains a fact that for the majority of our young people the college is not only in loco parentis but also in loco ecclesiae. The present struggle in domestic as well as world affairs, is a struggle for the human soul.”16

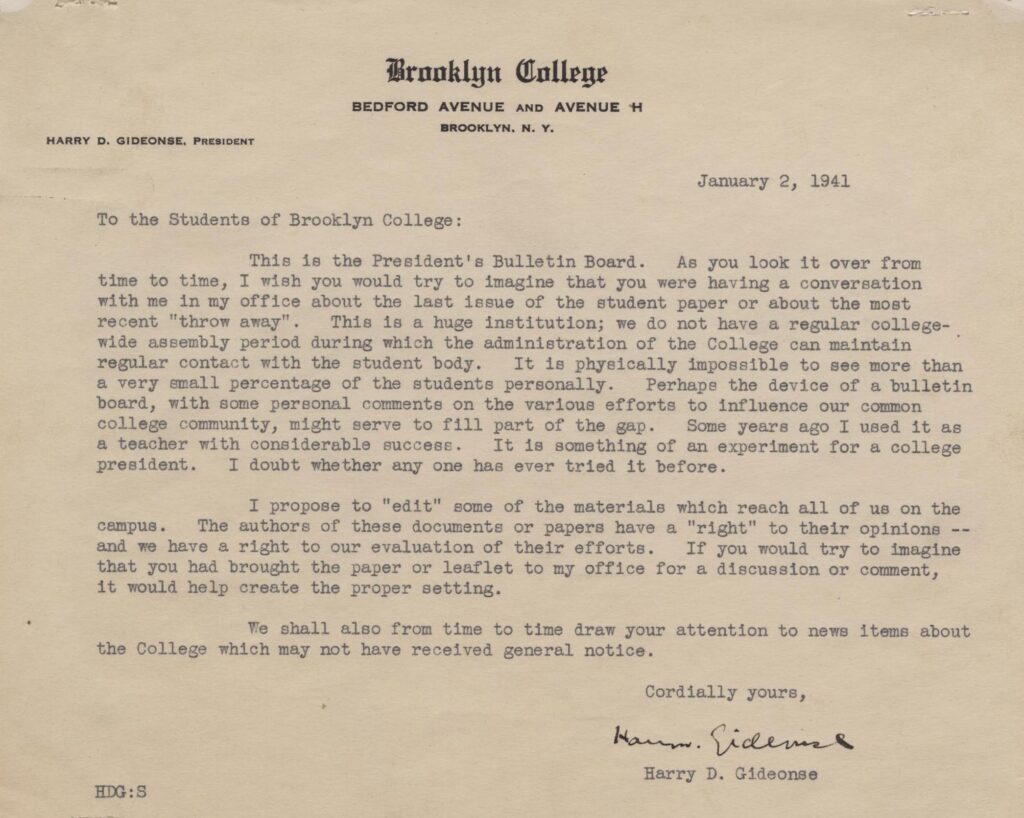

Memo detailing the purpose of the President’s Bulletin Board in Boylan Hall. Gideonse used this Bulletin Board to post student flyers and articles which expressed views contrary to his own. Using a red pen, Gideonse made corrections and wrote stern commentaries on the offending documents. As he stated in the memo, “The authors of these documents or papers have a ‘right’ to their opinions — and we have a right to our evaluation of their efforts.” At times students brazenly covered the display with their coats. The Papers of Harry Gideonse, Brooklyn College Archives.

If Gideonse acted like a parent to his students, he at times treated the faculty the same way. While the curriculum was under the purview of the Faculty Council, Gideonse’s call for sweeping curriculum changes in tune with his vision for the College resulted in numerous clashes with faculty who felt that the President often overstepped his powers. In his quest to hire like-minded faculty and expand course offerings, Gideonse appointed outside faculty to chair departments, interfered in departmental elections, and gave raises in a manner that some professors found to be arbitrary. According to Jacob Fischel, staff “suspected that certain faculty curried favor with the administration in return for prime consideration when the time approached to grant promotions and special increments. In turn, others believed that the President used the powers of his office as a wedge to advance, through the faculty committees, the passage of his program. Not surprisingly, a segment of the faculty emerged who viewed the Gideonse years as a period of great demoralization on the Brooklyn campus.”17 The red-scare investigations added to this hostile atmosphere. As we shall examine in future posts, Gideonse used all his available powers to ferret out Communist staff members. If faculty members, like Harry Albaum and Bernard Grebanier, confessed their sin of Communist affiliation, they would receive the protection of his office. However, Gideonse saw a refusal to testify as a sign of guilt and those faculty needed to be exposed and ousted from the College.

For 27 years, Gideonse’s firm and guiding hand directed the course of Brooklyn College. During this time, his writings and activities in such organizations as Freedom House brought national attention to his views on higher education and American democracy. Gideonse believed that freedom, whether in academia or in a democracy, could only survive if its adherents understood their responsibilities and possessed an inner discipline along with a shared sense of morality. “Freedom,” Gideonse wrote, “is not the absence of restraint or the right to do ‘as you please.’ It is the presence of responsible choice. It is anchored in a capacity for self-control. Free society and its opposite cannot be distinguished by the absence of authority in one case and its presence in the other. It is, rather, a question of inner checks in the first case and external control in the other. This is not merely a question of intellectual understanding; it is essentially a matter of moral commitment.”18 While his ability to influence national politics was minimal, as President of Brooklyn College, he had the authority to put his philosophy into practice. Gideonse’s legacy, however, will continue to be one of perspective.

Endnotes

1 Thomas Evans Coulton, A City College in Action (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1955); The Vanguard Collection, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; The Papers of Harry Slochower, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

2 Jacob Fischel, Harry Gideone: The Public Life, PhD diss. (University of Delaware, 1973), 443.

3 Fischel, 2-23

4 Walgreens Hearings, 1935, Box 2, Folder 5, The Papers of Harry Gideonse, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

5 Fischel, 133.

6 Fischel, 131-132.

7 Correspondence 1938-1958, Box 14, Folder 5, The Papers of Harry Gideonse, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

8 Inauguration of Harry D. Gideonse, Box 13, Folder 2. Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

9 Inauguration of Harry D. Gideonse, Box 13, Folder 2. Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

10 “College Bans Browder,” New York Times 4 December 1939:1; “Beacon Ban Lifted After Two Weeks,” Beacon 10 February 1941: 1; “Student Leaders Fight Against Suspension,” Beacon 10 February 1941: 1.

11 “Brief to Charge Coercion: Intimidation Document Hits Faculty Committee,” Beacon 17 February 1941:1; “Democracy on the Campus?” Box 2, Brooklyn College Handbill Collections, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

12 “Dr. Butler Warns His Faculty Not to Abuse Academic Freedom,” New York Times 4 October 1941: 1; “Eight at Columbia Challenge Butler,” New York Times 6 October 1941: 39; “Butler Reassures Faculty on Rights,” New York Times 11 October 40: 23.

13 Academic Freedom Files, Box 15, Folder 4, The Papers of Harry Gideonse, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

14 Robert Cohen. When the Old Left was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement, 1929-1941 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 103.

15 Cohen, 60-61.

16 Annual Report of the President for the Years 1940-1941, Box 1, bound. Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

17 Fischel, 243.

18 Harry Gideonse, “Academic Freedom: Challenge and Clarification,” in Against the Running Tide, ed. Alexander Preminger (New York: Twaine Publishing: New York, 1967), 142.