Brooklyn College adapted its curriculum and added coursework to meet the needs of a country at war. Faculty Council approved dozens of new classes designed to prepare students to fight on the front lines, work for government agencies and research laboratories, and assist on the home front. Community members and students could choose from a plethora of non-credit-bearing classes to learn such skills as first aid and map reading. Faculty also taught courses to servicemen stationed on or near the Midwood campus. BC President Gideonse wrote that in a time of war, a college is not a luxury but rather a necessity: “A war is not fought merely with guns and technology. The mechanical skills rest on a sound grasp of the basic sciences, without which the mechanic or the manipulator is degraded to the function of a pure robot. Most important of all: the techniques and the instruments are used to achieve a human purpose, and it is precisely in the cultivation of the values of free men that the chief objectives of the liberal arts curriculum are to be found.”1

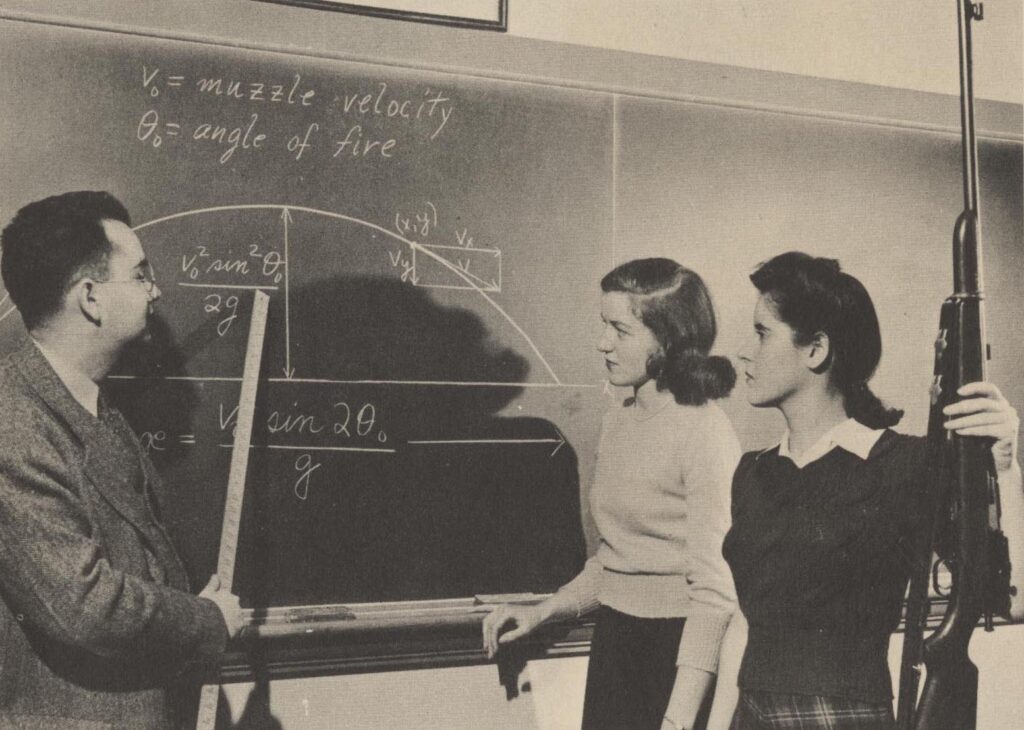

Faculty Council approved approximately 40 undergraduate classes related to the war effort and civilian defense. Offerings included Chemical Explosives, Chemical Warfare, Cryptography, Ballistics, Navigation, Meteorology, Hispano-American Literature, Radio, Military History, International Organization, and Aerodynamics. Students could also enroll in elementary Japanese and Russian language classes, while students in the Department of Design (Art) could sign up for a 12-week Camouflage course.2

Annie Get Your Gun…and Your Books! Photo of a BC Ballistics Class (Math 35). Brooklyn College Scrapbooks, Brooklyn College Archives.

Photo of Dorothy Toplitzky from the 1943 Broeklundian. In 2022, Blum was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame.

Gideonse wrote: “Our Brooklyn College graduates helped to map the Alaskan Highway; they are staffing the foreign language departments of our censorship organizations and of the armed forces; they are teaching mathematics to air cadets, and they are, of course, doing technical and specialized work in every branch of the armed forces.”3 Celebrated as one of the “Queens of Code,” Dorothy Toplitzky Blum ’44, a Chemistry major at BC, took the newly offered Cryptography course and, after graduation, worked in Washington in the Signal Intelligence Service deciphering enemy codes. After the war, she became a high-ranking manager at the NSA and encouraged women to pursue careers in computer technology.4

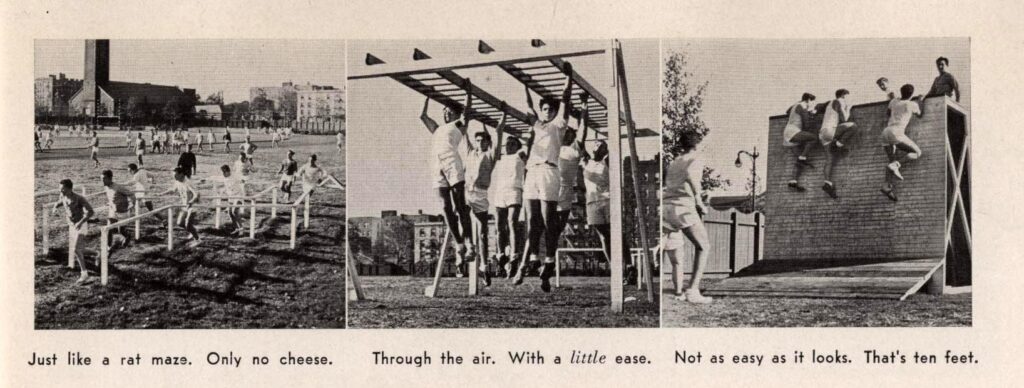

To prepare men for basic training, members of the BC Facilities staff constructed a ranger course on the athletic field using mainly telephone poles discarded by the Bell Telephone Company. As part of the advanced Men’s Hygiene classes (Hygiene 5.1-5.3) instituted during the war, students jumped hurdles and ditches, climbed walls and ladders, balanced on poles, and crawled under nets. According to the President’s Annual Report for 1941-1942, “In addition, there has been constructed at one end of the indoor swimming pool in the Gymnasium Building, a unit resembling the side of a ship. Ropes hanging from it allow the men either to ease their way into the water, or to climb ‘aboard.'”5

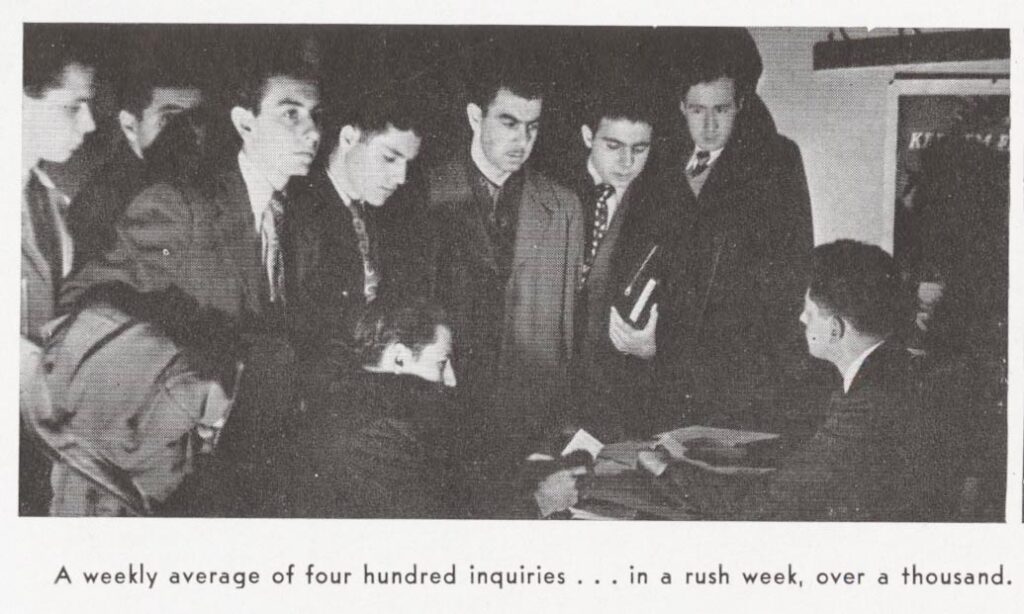

In 1942, the Office of War Service Counselor was established to provide guidance to students facing the draft, seeking a deferment, or enlisting. Headed by Professor Austin Wood of the Psychology Department, this office collaborated closely with deans and faculty members, providing curriculum guidance and helping students to navigate changes made to grading and graduation requirements. During the war, students could receive credits for classes if they attended for at least ten weeks or attain a degree if they were fewer than 12 credits short of graduation. To help students graduate faster, an undergraduate could enroll in up to 18 credits per semester, and summer school was instituted for the first time. Faculty Council also approved accelerated 10.1 sections of undergraduate classes for men about to be drafted and veterans who returned to college after a semester started.6 By 1943, 400 students per week came to the office in need of counseling.7 In September 1944, the office was renamed the Veterans and War Counseling Office to meet the needs of both veterans and those entering the armed forces.8

Men lining up for appointments at the Office of War Service Counselor. 1944 Broeklundian jr, Brooklyn College Archives.

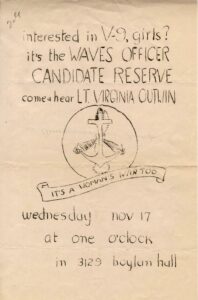

Flyer announcing a recruitment event for the women’s reserve unit of the Navy known as the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). Changes to the V-9 regulations permitted seniors to enroll in the officer training program before graduating from college. Records of the Brooklyn College War and Veterans Affairs, Brooklyn College Archives.

Women who were considering enlisting in the auxiliary branches of the Army, Navy, or Coast Guard (WAACS, WAVES, and SPARS) also received guidance from the Office of War Service Counselor. As the war progressed, women made up the majority of the student body. Female students looked for ways to contribute to the war effort, and the government needed college-educated women to work in research labs, in administrative jobs, and on the home front. In 1942, the President’s Advisory Committee on Modification of the Curriculum for Women to Meet Defense Needs was formed. Faculty on this committee concentrated on modifying existing college resources to prepare junior and senior women for employment in war-related positions, including chemists, physicists, accountants, nurses, administrators, linguists, and mail examiners (censors). The recommendations of this committee led to the establishment of the Home Economics department in 1947.9 Even though the college lacked a nursing program, Women’s Hygiene Chair Sally Kutz developed an eight-week pre-clinical program for student nurses in the summer of 1942 to help alleviate the country’s nursing shortage. 10

Dozens of non-credit-bearing classes and workshops were open to BC students and community members. BC faculty, staff, and alumni volunteered to teach such classes as Air Raid Precaution, Conservation of Clothing, American Red Cross First Aid, Map Reading, Nutrition, Canteen, and Home Nursing. During the 1941-1942 academic year, eighteen hundred community members enrolled in 68 defense courses, with 1345 registered in first aid classes.11 BC undergraduates could drop in on weekly conversation sessions in different European languages or take an advanced hiking course to prepare for long marches.12

BC Rifle Club advertised free shooting lessons for co-eds. Vanguard April 30, 1943, page 8. Brooklyn College Archives.

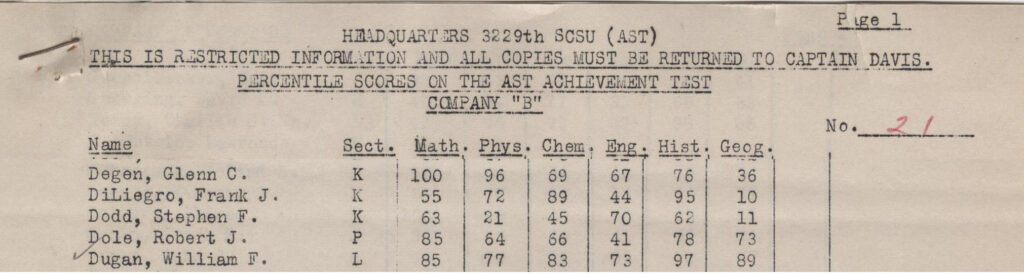

Active servicemen also took classes on campus and used the athletic facilities. In November 1943, 401 soldiers enrolled in the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) were assigned to Brooklyn College. From December 1943 until April 1944, these soldiers attended classes taught by BC faculty members and lived in dormitories set up in Boylan Hall, Ingersoll Hall, and the Gymnasium. Part of the cafeteria became a mess hall for the men, while washrooms and general office space were temporarily reassigned to the program. Ninety students from this program did not complete their coursework at BC, primarily because of failing grades. After the army curtailed the program’s size, the soldiers were reassigned to other colleges or sent to the front.13 US Senator and Presidential Candidate Robert Dole (1923-2021) was one of the ASTP soldiers stationed at Brooklyn College. After the ASTP left campus, 200 Coast Guardsmen from Manhattan Beach came to enjoy the festive atmosphere of the BC canteen every Friday night.14 In addition to the ASTP and Coast Guardsmen on campus, Signal Corps reservists took Engineering Science Management Defense Training (ESMDT) classes in radio fundamentals under Prof. Morris Weinrich (Physics).15 Soldiers from Floyd Bennet Field learned lifesaving skills and took swimming lessons in the Gymnasium’s pool.16

Bob Dole’s final grades in the ASTP program, April 1944. Records of the Brooklyn College War and Veterans Affairs, Brooklyn College Archives.

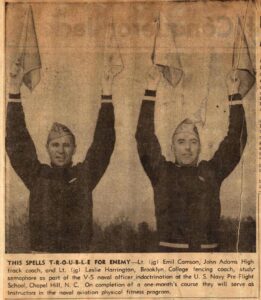

Brooklyn College Fencing Coach Leslie Harrington (right) demonstrates the use of flags as signals, part of his training at the US Navy Pre-Flight school in North Carolina. Brooklyn College Scrapbook Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

All these initiatives were successful due to the commitment of BC faculty and staff who took on extra responsibilities and contributed to the war effort both on and off campus. On campus, they served as air raid wardens, taught visiting soldiers and pre-clinical nurses, and volunteered as instructors for civilian defense classes. Off campus, they taught students enrolled in the Farm Labor Project and gave lectures to community groups as part of the Victory Speakers Bureau.17 Because of their academic skills, many faculty members took leaves of absence to work at research facilities or became instructors on military bases. As a result, department chairs often scrambled to find replacement instructors for classes already in session. For example, Professor Harry Albaum (Biology) worked at the Chemical Warfare Center of the Army Service Forces in Maryland; Melba Phillips (Physics) taught in the Army Air Corps and worked in the Radio Research Laboratory at Harvard University; and Dr. Irwin Alters (Hygiene) became the Kweiyang (Guiyang) Military Hospital Director and taught classes at the city’s Chinese Medical Training Center. Others saw active duty on the front lines. Bursar Samuel Katz, a major in the US Army, was awarded the ATC (Air Transport Command) ribbon and EAMEC (European – African – Middle Eastern Campaign) medal.18

During the war, the faculty and administration carefully weighted the changes to the curriculum, grading, and graduation requirements. While graduation and credits in some cases were accelerated, the decisions were made on a case-by-case basis. The objective was not to cheapen the degree but to prepare students for war and the transition back to either academic or professional life. Gideonse wrote: “We should do everything in our power, and compatible with the quality of academic achievement, to give the boys who are about to see their educational career interrupted by the call to national service a chance to leave the college with a sense of fulfillment and achievement rather an impression of perhaps permanently impaired continuity.”19

BC students working with alidades and plane tables in a Military Topography class (Geology 7). Brooklyn College Scrapbooks, Brooklyn College Archives.

Endnotes

1 Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, page 5, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

2 “Defense Courses Announced,” Vanguard 1 May 1942, page 1; Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, pages 30-31, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Brooklyn College in Defense and War Program” Box 557, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; Minutes of the Brooklyn College Faculty Council, 1940-1945, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

3 Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, page 5, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

4 Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame. Dorothy Toplitzky Blum. https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshallfame/html/blum.html

5 Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, page 31, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

6 Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, pages 32-39, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

7 Thomas Evans Coulton, A City College in Action (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1955), 160.

8 Annual Report of the President, 1942-1949, page 10, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

9 President’s Advisory Committee on Modification of Curriculum (1942 – 1943), Box 478, Folder 4, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

10 Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, page 27, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

11 Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, pages 41-42, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Brooklyn College in Defense and War Program” Box 557, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

12 “All College Drive for Victory Classes Begins on Monday,” Vanguard 20 March 1942, page 1; “Brooklyn College in Defense and War Program” Box 557, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

13 Army Specialized Training Program, Box 1, Folders 1-5, Records of the Brooklyn College War and Veterans Affairs, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Slashing of ATSP to Hit BC Unit,” Vanguard 28 February 1944, page 1; “ASTP Contract for Campus Ended,” Vanguard 20 March 1944, page 1.

14 “Beachhead Established,” Vanguard 11 October 1944, page 4.

15 “Gov’t Sponsors Radio Courses for Reserves.” Vanguard 2 September 1942, page 8; Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, page 27, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

16 Annual Report of the President, 1941-1942, page 26, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

17 Committee on Speakers Bureau, Box 463, Folder 7, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

18 Annual Report of the President 1942-1947, Appendix b, Box 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

19 “Brooklyn College in Defense and War Program” Box 557, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.