While the Negro Study Forum’s level of activity in 1940 continued to be on par with previous years, it would be the club’s last year on campus. On November 29, 1940, the Vanguard reported that the Negro Study Forum would be reorganized as the Harriet Tubman Society to center “its activities around a revised, militant program.”1 There is no further information in the archival record as to why this group was reorganized under a new name. The Forum’s activities in 1939 and 1940, including co-sponsoring events with the American Student Union (ASU) and sending delegates to the 3rd National Negro Conference in Washington, suggest an increased rather than diminished militancy prior to reorganization.

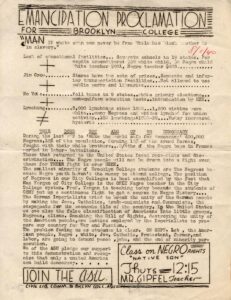

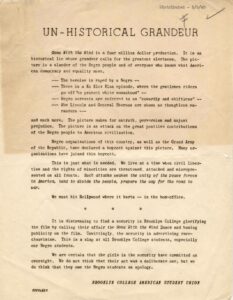

The ASU, although weakened politically and smaller in membership after adopting its stance on neutrality following the Nazi-Soviet Pact, remained active on campus.2 Mainly concerned with keeping America out of the war, the ASU also distributed flyers focused on academic freedom and discrimination. In March 1940, the ASU criticized BC sorority Upsilon Phi’s Gone with the Wind-themed dance and called on the sorority to apologize to the African American students on campus. The ASU flyer described the motion picture as a “slander of the Negro people” and “an attack on the great positive contributions of the Negro people to American civilization.”3 During the summer of 1940, the ASU distributed a flyer titled “The Emancipation Proclamation of Brooklyn College,” an anti-war leaflet detailing racism and violence against African Americans and calling for unity among all minority groups to keep America out of the war.4

The Negro Study Forum stood in solidarity with the ASU after the College refused to allow communist leader Earl Browder to speak on campus. On November 29, 1939, Bertram Alves, president of the Negro Study Forum, spoke at the ASU rally protesting Browder’s ban. At the rally, Alves “called for the defense of all minority rights.”5 Alves, who attended Brooklyn College from 1938 to 1940, was a member of the Harlem Youth Congress, chaired the Harlem NYC Youth Council, and in 1944, was elected to the permanent Student Conference Committee at the first annual student conference of the NAACP. After WWII, he became a leader of the United Negro and Allied Veterans of America and was the business manager for Paul Robeson’s civil rights publication, Freedom.6

In April 1940, the ASU and the Negro Study Forum co-sponsored an event supporting the passage of a federal anti-lynching bill. The featured speaker was Negro Youth Congress leader Louis Burnham, CCNY alumnus and husband of BC alumna Dorothy Challenor.7 James B. Knight, president of the Forum, was one of 29 students from 25 different student clubs listed on the Committee for the Anti-Lynch Bill’s flyer, showing broad campus support.8 Also, in 1940, nine Brooklyn College students, including Negro Study Forum members Fitz Squires ‘47 (vice president) and Rose Fleming ’42, attended the 3rd National Negro Congress convention in Washington.9

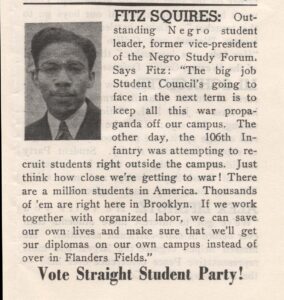

Fitz Squires’ candidate statement, Student Party pamphlet, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives.

On campus, the ASU hoped to regain political power by campaigning for Student Council positions under the guise of the Student Party. Viewed as a front for the ASU, the Student Party failed to win campus elections following the Nazi-Soviet Pact, including those held during the spring of 1940.10 That semester, the Student Party’s candidate for vice president was Fitz Squires. In a Student Party pamphlet, Squires wrote, “The big job Student Council’s going to face in the next term is to keep all this war propaganda off our campus…If we work together with organized labor, we can save our own lives and make sure that we’ll get our diplomas on our own campus instead of over Flanders Fields.” The party’s platform, which included keeping America out of an imperialist war, also called for an African American history class at Brooklyn College and supported anti-lynching and anti-poll tax legislation.11

Squires, a communist, would play a leading role in two ASU-led student walkouts, including the unauthorized May 24, 1940 peace strike, which resulted in the temporary suspension of the ASU and the affiliated Peace Congress. Squires was listed as a member of the Peace Congress on both the strike flyers and in memos written by Custodial Engineer Arthur Hillary, who spied on “subversive” events for the college administration.12 At subsequent rallies, Squires spoke out against the ASU suspension.13 Following Germany’s June 1941 invasion of the USSR, Squires, along with other communist students and members of the ASU, became pro-war. Squires took a military leave of absence from his studies in 1942 and joined the Tuskegee Airmen, for which he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Squires was an active member of two Communist Party organizations: the American Youth for Democracy and the Labor Youth League.14

After the demise of the Negro Study Forum, the first event of the Harriet Tubman Society centered on segregation in the National Defense Program with Louis Burnham invited back as the inaugural speaker. James Bynoe ‘42 was elected president, with Fitz Squires returning as VP.15 While flyers and clippings regarding the Society’s activities during the war have been found in the Archives, this is not the case for the Negro Problem’s Club. After the Beacon, the paper of the Evening Session ceased publication in February 1942, the archival record is silent on the activities of the Negro Problems Club. Before Pearl Harbor, the Club held meetings to discuss how another world war would affect African Americans. In 1938, the Negro Problems Club invited George Streator, CIO organizer and a former assistant editor of The Crisis, to speak on the “Negro and the Current War Threat.” Tom Jones, a leader in the Brooklyn Negro Youth Federation and the American Youth Congress, spoke at a March 1941 meeting cosponsored by the ASU and the Negro Problems Club on “The Negro and the War.”16

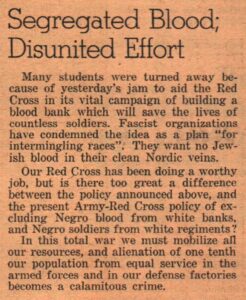

Once the war began, two discriminatory practices came to the forefront: blood donation and segregation in the armed forces. Until 1950, the American Red Cross segregated blood donations based on race. The donation program, which began in 1941, initially excluded African Americans, but once they were permitted to donate blood, those donations were kept separate from the blood donated by whites, with some southern states continuing this practice until the 1960s and 70s.17 While Brooklyn College Professor Frederick Maroney denied this practice to encourage students to donate more blood, the Harriet Tubman Society and other student clubs criticized the Red Cross. A Vanguard editorial from April 1942 denounced the Red Cross and compared the separation of blood to the treatment of Jews by the Nazis. In the same editorial, the Vanguard also condemned segregation in the US military and the inability of African Americans to get high-paying defense industry jobs: “In this total war we must mobilize all our resources, and alienation of one-tenth of our population from equal service in the armed forces and in our defense factories becomes a calamitous crime.”18

Calls to end segregation in the US military intensified on campus when African American students Charles de Leon ‘43 and Irving Bishop ‘47 (the only African American on the BC football team) tried to enlist as marine reservists at a campus recruitment event. Two years earlier, de Leon, a former president of the Negro Study Forum, had spoken out against NYU’s refusal to permit an African American student to play in a football game held in Missouri in 1940. The military recruiters informed de Leon and Bishop that their applications could not be accepted since there were no African American marine corps units.19 The Student Council passed a resolution condemning this incident and circulated a petition on campus urging men to sign, pledging that they are “willing to serve with troops composed of all segments of the population.”20

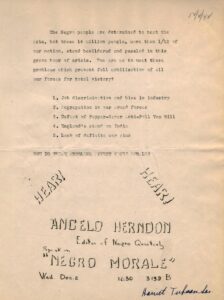

Flyer announcing a Harriet Tubman Society event featuring Angelo Herndon. Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives.

The Harriet Tubman Society sponsored campus-wide rallies and hosted meetings calling for the integration of the US military.21 At an April 1942 joint meeting of the Harriet Tubman Society and the Sociology-Anthropology Club, noted sociologist Ruth Benedict spoke on race and the war. Critical of US policy, she urged students to conduct fieldwork in their communities to document discrimination against African Americans.22 In December 1942, African American communist Angelo Herndon spoke before the Harriet Tubman Society on how “Negro Morale” was affected by job discrimination, segregation in the military, and the defeat of the poll tax bill. The blurb on the event flyer placed the event into context: “The Negro People are determined to beat the axis, but these 14 million people, more than 1/10 of our nation, stand bewildered and puzzled in this hour of crisis.”23

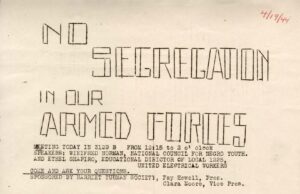

At that meeting, white and African American students voted to circulate a petition on campus calling for a voluntary mixed brigade.24 This petition drive continued throughout the winter of 1943 with the Harriet Tubman Society denouncing segregation in the military as a violation of “the Constitution in spirit and actuality.”25 In April 1944, the Society held a “No Segregation in Our Armed Forces” rally as part of a larger American Youth for Democracy campaign. Speakers include Winifred Norman, who urged BC students to support the American Youth for Democracy’s (formerly the Young Communist League) national campaign to integrate the armed forces, and Ethel Shapiro of the CIO, who argued that workers’ rights would be in jeopardy until there was equality for blacks and whites in both factories and the army.26

Harriet Tubman Society flyer calling for an end to segregation in the US military. Handbill Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

The Harriet Tubman Society was also at the forefront of the campus campaigns to add an African American history class to the Brooklyn College curriculum and advocated hiring African American faculty. The first African American history class in what is now known as CUNY was taught at City College in 1937 after Louis Burnham, then the president of CCNY’s Frederick Douglass Society, led the successful fight for this class and for an African American to teach it. As a result, Max Yergan, a leader in the Harlem branch of the Communist Party, became the first African American hired to teach in the municipal college system. He, however, was hired on a contractual basis and was not a full-time professor. Yergan would become one of approximately 40 public college employees who lost their jobs during the investigation into subversive activities at public colleges by New York State’s Rapp-Coudert Committee.27

Getting a course in African American history at Brooklyn College proved more difficult since Brooklyn College President Harry Gideonse opposed the idea. At a November 1944 meeting of the Chapin and Spence Schools in NYC, Gideonse argued that the contributions of minority groups should be added to existing classes rather than creating special courses devoted to a particular race. Critical of such classes already in existence, including the one at City, Gideonse stated, “Almost invariably it works out badly. It tends to create the group if it doesn’t already exist. It tends to make other groups crystalize their attitudes and make them think of the other as a group.”28

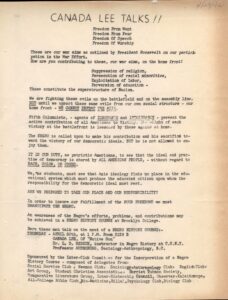

On April 30, 1942, actor and civil rights activist Canada Lee spoke at an event sponsored by the Inter-Club Committee for the Incorporation of a Negro History Course at BC. Handbill Collection, Brooklyn College Archives.

Calls for an African American history class began at Brooklyn College during the 1930s when left-wing groups, including the NSL and ASU, promoted the recognition of the contributions of African Americans in US history. In 1939, the Beacon reported that the Negro Problems Club would collaborate with the Negro Study Forum to campaign for an African American history class. These clubs, it was reported, had the support of the Student Council and the ASU. The Negro Problems Club planned to hold African American history classes at its weekly club meetings if the administration failed to expand the curriculum.29

During the war, the Harriet Tubman Society revived this effort, and as with the integration of the armed forces, the Society circulated petitions on campus and was the original sponsor of the Committee for a Negro History Course and Negro Teachers. This 15-club committee which included Hillel, the Newman Club, and the Sociology-Anthropology Club, sponsored an event in April 1942 to bring attention to the fact that “discrimination has no place in a democracy, and this applies particularly in the war against fascism. A Negro history course will show the part the Negro people have had in building and fighting for our democracy.”30 Unfortunately, the campaign achieved only partial success with a class added to the graduate (1942) and undergraduate (1944) offerings in the Sociology-Anthropology department.31

Newly elected City Councilman Adam Clayton Powell jr. brought the fight to end discriminatory hiring practices at the municipal colleges to City Hall. Powell, the first African American elected to the New York City Council, introduced a resolution in February 1942 calling for an investigation into the hiring practices at the four city colleges (City, Hunter, Queens, and Brooklyn). At that time, there were no African American professors among the 2232 faculty members at these institutions.32 African Americans had only been hired to temporary, contractual positions, rather than appointed the titles of instructor or professor, which were full-time positions and after 1940 tenure tracked. At the hearing held on February 13, 1942, President Harry Gideonse denied any racial bias in hiring faculty at Brooklyn College and stated that he was aware of only four African Americans who applied to teach at Brooklyn College, with one applicant turning down a job for a higher salary at another school.33

When Adam Clayton Powell jr. came to campus to speak about hiring practices at a meeting of the Harriet Tubman Society, the Student Council voted not to endorse Powell’s talk because of the Councilmember’s alleged ties with the Communist Party.34 Throughout the 1930s, Powell supported the activities of the Communist Party in Harlem when he viewed a particular campaign as beneficial to the community and openly criticized the Party when he disagreed with their policies. While the Communist Party did support his election campaign, Powell was never a member.35

Although Powell’s resolution lost momentum, in September 1944 Brooklyn College hired Marion Cuthbert to teach in the Sociology-Anthropology department. Cuthbert became not only the first African American faculty member at Brooklyn College but also the first African American to be part of the permanent staff at the four city colleges (City, Hunter, Queens, and Brooklyn). A poet, activist, and scholar, Cuthbert taught in the Sociology-Anthropology Department until her retirement in 1961. According to the book Harlem Renaissance and Beyond, “In all of her work, Cuthbert is skillful in pinpointing problems where race and gender intersect and where the struggles of women of color differ from those of white women and black men.”36

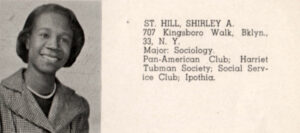

Although the Negro Student Forum, the Negro Problems Club, the Harriet Tubman Society, and allied clubs raised awareness of African American issues, Shirley Chisholm ‘46, who attended Brooklyn College during the war, noted that there was still a long way to go. Chisholm joined the Harriet Tubman Society during her sophomore year. She recalled, “There I first heard people other than my father talk about white oppression, black racial consciousness, and black pride.”37 Studying to be a teacher because she felt that no other jobs would be open to her as an African American woman, she recalled that African American students sat by themselves in the cafeteria and remarked on both the racism experienced by African American students and sexism experienced by women, regardless of race, particularly when they ran for Student Council. Chisholm volunteered in the student government campaigns of female undergraduates, including that of Georgiana Pearl Graham ’44, an African American student and Negro Problems Club member who ran for vice president of the Student Council in 1943.38 After graduating from Brooklyn College, Chisholm became the first African American woman to serve in the US Congress and was the first woman to seek the Democratic Party’s nomination for president in 1972.39

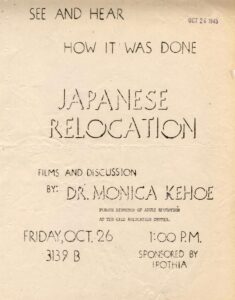

Because African American students “were not welcomed in social clubs,” Chisholm and her classmates created IPOTHIA (In Pursuit of the Highest in All), an inter-racial sorority in 1944.40 Toward the end of the war, IPOTHIA sponsored a talk by Dr. Monika Kehoe, the Assistant Dean of Women at BC from 1944-1946. As the former Adult Education Director at a relocation camp for Japanese Americans in Arizona, Dr. Kehoe and her partner Karen Kehoe, who also worked at the camp, were critical of the US government’s treatment of Japanese Americans.41

After the war, it would be more than two decades before African American and Latinx students brought issues of race and inequality back to the CUNY campuses. While the student movement of the 1960s has been widely researched and documented, the revolutionary spirit of their Depression-era counterparts has been largely ignored. It is hoped that these blog posts encourage students to delve deeper into the activities of the Negro Study Forum, the Negro Problems Club, and the Harriet Tubman Society.

Endnotes

1“Negro Study Forum Reorganized, Renamed,” Vanguard 29 November 1940, 2. The minutes of the Meeting of the Committee on Student Groups and Organization from December 2, 1940, reported that a new student club, Harriet Tubman Society, “intends to supplant,” the Negro Study Forum. See “Minutes of the Meeting of the Committee on Student Groups and Organization -December 2, 1940 and February 27, 1941,” Box 473, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

2For more on the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the ASU see Robert Cohen, When the Old Left was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement, 1921-1941 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 281-90, 293-295.

3“Un-historical Grandeur,” 9 March 1940, Box 747, folder 5. Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Gone with the Wind Dance,” 9 March 1940, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections. Although not listed in the flyer as one of the outside groups boycotting the film, in 1939 the Communist Party called for a boycott of Gone With the Wind, and Daily Worker editor Benjamin J. Davis, jr. led the picket line when the movie premiered in Harlem (Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression (New York: Grove Press, 1984): 299.

4“Emancipation Proclamation for Brooklyn College,” Box 747, Folder 1, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

5“American Student Union Protests Ban on Browder,” Vanguard 8 December 1939, 1.

6“Youth Congress to Conduct Congress,” New York Amsterdam News 21 June 1942, 12; “Harlem NYA Workers Organize Council to Halt Dismissals; Seek Reinstatements,” New York Amsterdam News 5 April 1941,17; “First Annual Student Conference,” Crisis 47, no. 5 (May 1940), 153-154; “E Harlem Vet Body Holds First Meeting,” New York Amsterdam News 18 May 1946, 10.

7“Burnham hits Klan Actions,” Vanguard 26 April 1940, 1.

8“Stop Lynching,” Box 747, Folder 4, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections. J.B. Knight attended BC for one year (1938).

9“Nine Brooklyn Students at Negro Congress,” Vanguard 3 May 1940; Naison, 288, 294-297. Note: The Congress, which declared its support of the ASU, hoped the convention would revitalize the organization after the collapse of the popular front, but lost support from moderate African Americans who viewed it as closely tied with the Communist Party. Fitz Squire’s sister, Eunice (Una) Squires was vice president of the Negro Problems Club in 1937. See “Nite Clubs,” Beacon 8 May 1937, 3.

10“First Convention of the Student Party, 11/30/38,” Box 749, Folder 3. Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives; “Court of Student Opinion,” Box 748, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Kingsmen-Fusion Sweeps 17 of 20 Posts in College-Wide Poll,” Vanguard 31 May 1940, 1; “Kingsmen-Fusion Gains First Big Election Victory in Class Vote,” Vanguard 11 January 40, 1. For more about the Student Party see “S.P. Dedicates Next Week to ‘Bill of Rights,’” Vanguard 3 May 1940, 1.

11Student Party Pamphlet, May 1940, Box 747, Folder 2, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

12“All Students Join the Anti-War Stoppage Friday at 10 am,” Box 747, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; ”Report on the Brooklyn College Peace Strike, May 24, 1940, Box 753, Folder 7, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “We Call upon the Students to Strike for Peace,” Box 747, Folder 3, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; Continuations Committee of the All College Peace Congress, “Rep. Coffee to Address Peace Congress Strike Tomorrow at 11, Box 747, Folder 6, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections (Squires is listed as a speaker); “Vanguard Exposes Peace Strike Committee, 5/14/40,” Box 748, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Louder Than Ever,” [May 1940] Box 747, Folder 4, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections (Squires listed as the Secretary of the United Peace Congress).

13See (Note: not exhaustive): “Defend Academic Freedom,” Box 747, Folder 5, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections (Squires listed as Chair of the Committee for Defense of Student Rights and Bertram Alves is listed as a supporter); “Demonstrate for Student Rights,” Box 747, Folder 6, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Stop the Rapp Investigation,” Box 747, Folder 6 Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “We Call Upon the Students to Unite for Peace,” Box 747, Folder 4, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections (Note: Squires is listed as a member of the Emergency Peace Mobilization Committee formed following the suggestion of the American Youth Congress).

14Andrea Siegel, “In Memory of Fitz A. Squires 1920-2014,” The Bronx Chronicle 8 January 2015. https://thebronxchronicle.com/2015/01/08/memory-fitz-squires-1920-2014/; United States, Congress, House Committee on Un-American Activities, Testimony of Walter S. Steele regarding Communist activities in the United States. Hearings before the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eightieth Congress, first session, on H. R. 1884 and H. R. 2122, Bills to Curb or Outlaw the Communist Party in the United States, 76; United States, Congress, Senate, Communist Tactics in Controlling Youth Organizations: Hearings Before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee To Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, Subcommittee Investigating Communist Tactics in Controlling Youth Organizations, Eighty-Second Congress, First Session and Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session, on Apr. 12, June 12, 1951, Jan. 16, Feb. 27-29, Mar. 5, 24, 27, 1952, 224.

15“Negro Study Forum Reorganized, Renamed,” Vanguard 29 November 1940, 2. Bynoe was also the President of the Club to Defend Higher Education, a student group formed to fight for academic freedom in the wake of the Rapp-Coudert investigation. For more on James Bynoe see “Why Come to the Student-Faculty Jamboree, 5/29/41” Box 748, Folder 7, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Suspensions at BC, 6/6/41,” Box 748, Folder 7, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Fair Play, 12/2/41,” Box 748, Folder 7, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Tubman Club Hits NYU Jim Crowism,” Vanguard 24 March 1941, 3.

16“Streator to Speak at Negro Problems Club,” Beacon 28 March 1938, 4; “Tom Jones AYC Leader Talks on the Negro and the War,” Beacon 24 March 1941. See also “Negro and the War Topic at Symposium,” Beacon 18 December 1939, 1; “Night Clubs,” Beacon 25 May 2936, p3.

17“The Color of Blood: Red Cross Reflects on its Blood Collection History,” The American National Red Cross, 8 September 2021, https://www.redcross.org/about-us/news-and-events/press-release/2021/the-color-of-blood–red-cross-reflects-on-its-blood-collection-hiistory.html#:~:text=In%201948%2C%20the%20Red%20Cross,medical%20basis%20to%20do%20so; Thomas A. Guglielmo, “Desegregating Blood A Civil Rights Struggle to Remember,” pbs.org, 4 February 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/desegregating-blood-a-civil-rights-struggle-to-remember.

18“Maroney Discounts Blood Segregation,” Vanguard 24 April 1942, 4; “Segregated Blood; Disunited Effort,” Vanguard 17 April 1942,4.

19“Protest Negro Discrimination in Football,” Brooklyn College Student Handbill Collection; “Discrimination Hits Home,” Vanguard 27 February 1942, 1.

20“New Defense Head Elected,” Vanguard 20 March 1942, 1; “SC Circulated Petitions Protesting Segregation,” Vanguard 14 April 1942, 2.

21“Campaign for Mixed Brigade Inaugurated” Vanguard 9 April 1943, 1.

22“Ruth Benedict Talks On Race, War, Students,” Vanguard 27 March 1942, 1.

23“Hear Angelo Herndon, 12/2/42,” Box 748, Folder 13, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

24“Mixed Units,” 12/16/42, Box 748, Folder 13, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

25“Attention,” Box 748, Folder 13, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

26“Tubman Society Hears Equality Plea,” Vanguard 24 April 1944, 6. Note: On July 26, 1948, President Truman issued an executive order integrating the US military.

27Naison, 293-294; “Firing Dr. Yergan,” The Struggle for Free Speech at CCNY, 1931-1942, accessed on 8/10/2022, https://virtualny.ashp.cuny.edu/gutter/panels/panel17.html.

28Harry Gideonse, “Racial Tolerance and the Independent School” Proceedings of the Head Mistresses Association of the East, Annual Meeting, November 10-11, 1944, Box 11, Folder 1, Papers of Harry Gideonse, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

29“Clubs Support Campaign to Obtain Negro Courses,” Beacon 27 March 1939, 1. “Negro Problems Hears Law Talk,” Beacon 8 May 1939, 4; “History Bee Held By Negro Students,” Beacon 27 November 1939, 1. Note: The NSL also offered its own 6-week classes with tuition of 50 cents including Negro Folk Literature. See “National Student League Announces Ten Courses in School Curriculum,” Pioneer 6 March 1935, 6.

30“Propose Negro History Course,” Vanguard 8 May 1942, 4; “Tubman Petition Calls for Negro History Course,” Vanguard 4 December 1942, 6.

31Brooklyn College Bulletins, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; “Plan New Course on Negro Culture,” Vanguard 8 January 1943, 8. Note: The History Department first offered a class in African American history in 1970 (Course #43.5 Afro-American History).

32“City Colleges Face Negro Bias Inquiry,” New York Times February 1942, 21.

33“School Heads Deny Bias Against Negros,” New York Times 14 February 1942, 17.

34“The Powell Case,” Vanguard 27 March 1942, 1.

35See Naison, 172, 167-168, 307, 312-313

36“Marion Vera Cuthbert,” in Harlem Renaissance and Beyond, Lorraine Roses and Ruth Randolph (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990): 73. “First Negro Educator Joins Brooklyn College Faculty,” Brooklyn Citizen 26 September 1944; “Negro Educator Appointed to Boro College,” Brooklyn Eagle 26 September 1944, 3.

37Shirley Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 25

38“Dear Students,” Box 753, Folder 9, Records of the Office of the President, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections; Shirley Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970): 26; Barbara Winslow, Shirley Chisholm: A Catalyst for Change (Colorado: Westfield press, 2014): 23.

39For more on Shirley Chisholm see Shirley Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970); Barbara Winslow, Shirley Chisholm: A Catalyst for Change (Colorado: Westfield press, 2014); “The Chisholm Project: Brooklyn Women’s Activism From 1945 to the Present,” accessed on 27 August 2022, http://chisholmproject.com/; The Shirley Chisholm ’72 Collection, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections.

40Chisholm, 26; see also 22-28.

41“See and Hear How It Was Done,” 10/26/45, Brooklyn College Handbill Collection, Brooklyn College Archives and Special Collections. Robinson, Greg, “THE GREAT UNKNOWN AND THE UNKNOWN GREAT: Queer non-Nikkei figures in Japanese American History,” Nichi Bei, 3 April 2014, https://www.nichibei.org/2014/04/the-great-unknown-and-the-unknown-great-queer-non-nikkei-figures-in-japanese-american-history/. See also, Monika Kehoe, Lesbians over 60 Speak for Themselves (New York: Haworth Press, 1989). In 1945, Karen Kehoe wrote City in the Sun, a prize-winning novel about the Japanese American experience during WWII.